Analyzing COMmunication in Malware

If you follow me on Twitter (@0verfl0w_), you may have noticed a while back that I was analyzing a sample of Ursnif/Gozi/ISFB (which I will refer to as ISFB) and was confused as to how it was able to communicate with its C2 servers through a separate process, without injected DLL’s or process hollowing. I managed to locate a great article by Mandiant (here) from 2010 about how COM can be used to control a process, such as Internet Explorer, into performing certain actions.

In this post, I will be exploring the COM mechanisms that the latest versions of ISFB utilize in order to contact the command and control servers stealthily. I do have quite a long post going up (hopefully) in the next couple of weeks that goes into detail about this specific strain of ISFB, and the multiple unpacking stages it goes through before the final stage, so stay tuned for that!

What is exactly is COM?

According to Microsoft, “The Microsoft Component Object Model (COM) is a platform-independent, distributed, object-orientated system for creating binary software components.” To sum it up, COM allows programs to interact with each other through COM objects. This interaction can occur “within a single process, in other processes, and can even be on remote computers“, and the language that the program was written in does not matter – as long as it is able to create structures of pointers and call functions through those pointers, it is COM Compatible – meaning languages like Visual Basic and Java can use COM. If you want to learn more about COM, you can check out Microsoft’s own description and tutorials on it here.

As a result of the progression of technology, COM isn’t used as frequently anymore, and therefore when an analyst comes across a piece of malware utilizing this unfamiliar communication method, it may be difficult to pinpoint what is happening, and how. Static analysis is even more complex, unless you know what you are looking for – which is what this article is about.

COM Mechanisms and its use in the ISFB Loader

Second Stage Loader MD5: 5019f31005dba2b410b21c4743ef4e98

I have uploaded the first stage and dumped second stage loader to VirusBay, so that you can follow the steps if you want to. I will be focusing on the second stage loader, as that is where the communication with the C2 occurs. I will be analyzing it statically using IDA, although you can do it dynamically as well.

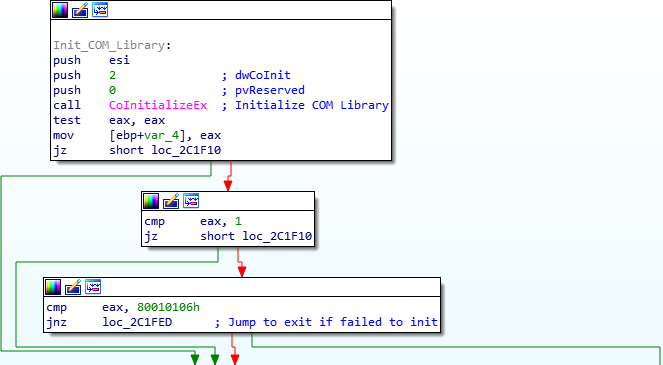

The first giveaway that malware could be using COM functionality for communicating with it’s C2 server is a call to CoInitializeEx. Calling this function will initialize the COM library so that the calling thread can utilize it’s functionality. Taking a look at the flow of this sample, it is clear that if initializing the library fails, it will exit – hinting that it heavily relies on the COM library being loaded successfully.

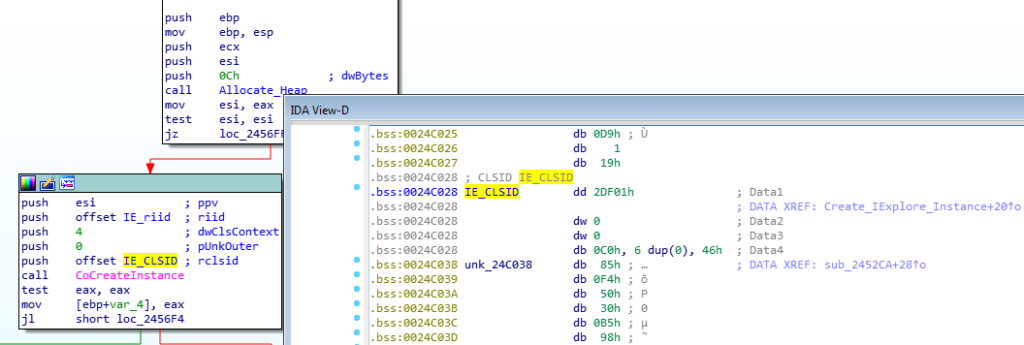

Once we have discovered it is initializing the COM library, we can search for calls to CoCreateInstance, as this spawns an uninitialized object of the class associated with a specific CLSID, meaning you will notice a new process being spawned after you step over this call. Whilst there are many cross references to CoCreateInstance in this sample, we are able to determine which one calls Internet Explorer based on the CLSID pushed before the function call. IDA will show you the CLSID based on how it looks in memory, and as a result, we can find the corresponding object that is called. But how?

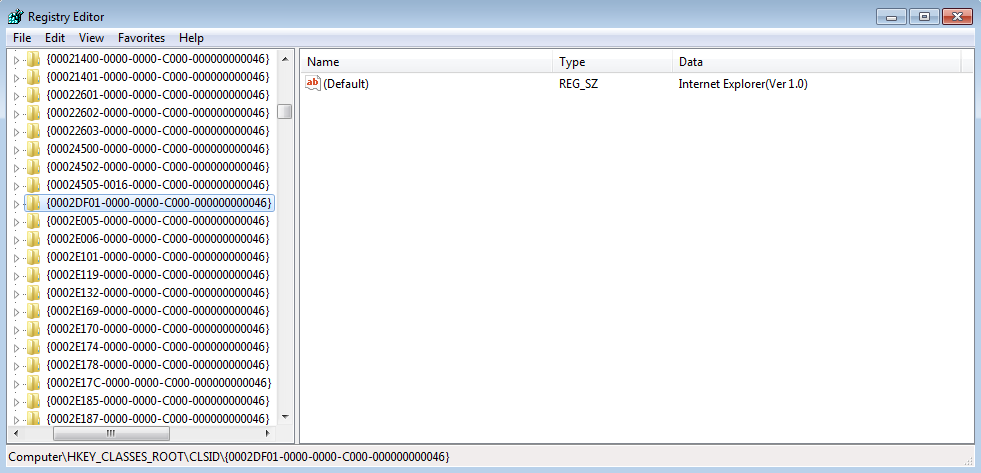

The CLSIDs of different objects are stored in the registry, and so whenever CoCreateInstance is called, the system checks the registry for the passed CLSID. From the image above, we can tell that the CLSID being utilized is {0002DF01-0000-0000-C000-000000000046}, which we can lookup in the registry. You can find a list of all the available CSLIDs at HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\CLSID. Once the CLSID has been located, it should reveal what process is being created, and in this case it is Internet Explorer (Ver 1). Moreover, the IE_riid that is being passed to the function informs us of the interface being used – in this case the riid being used is {EAB22AC1-30C1-11CF-A7EB-0000C05BAE0BE}, which when looked up in the registry reveals that it is the Microsoft Web Browser Version 1. When we google this riid, it comes up with results for the IWebBrowser interface.

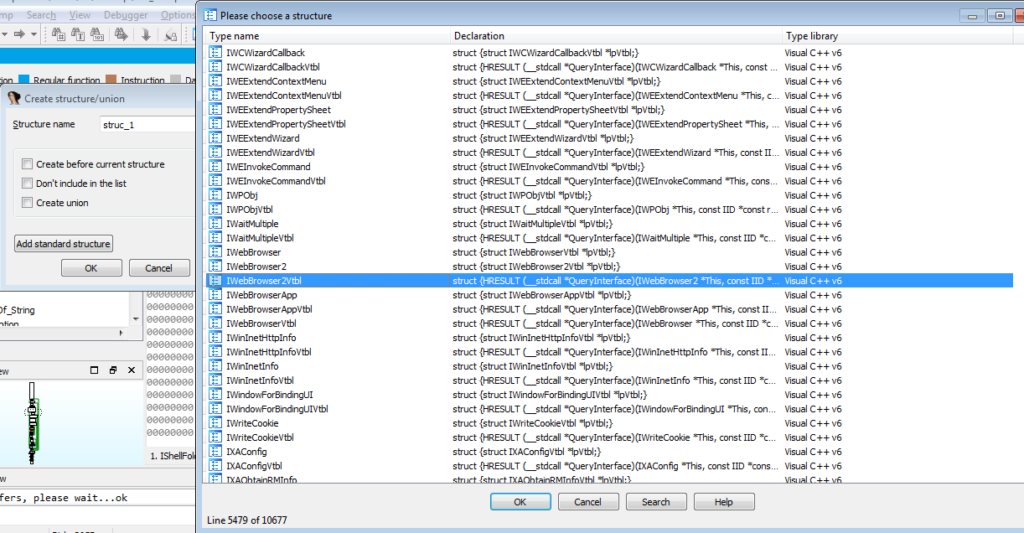

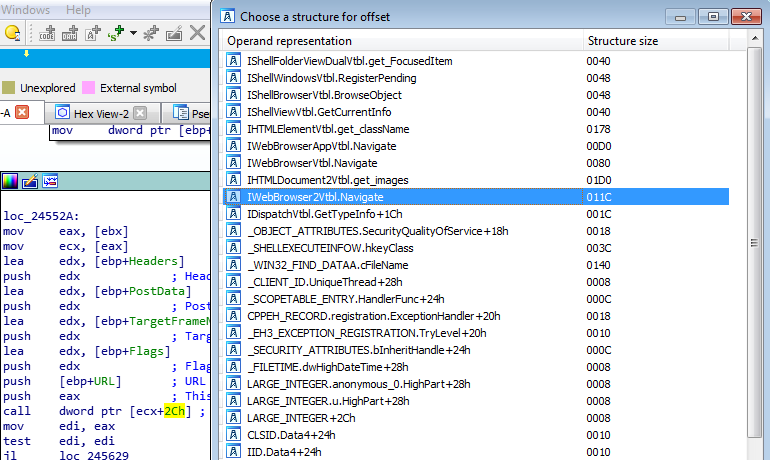

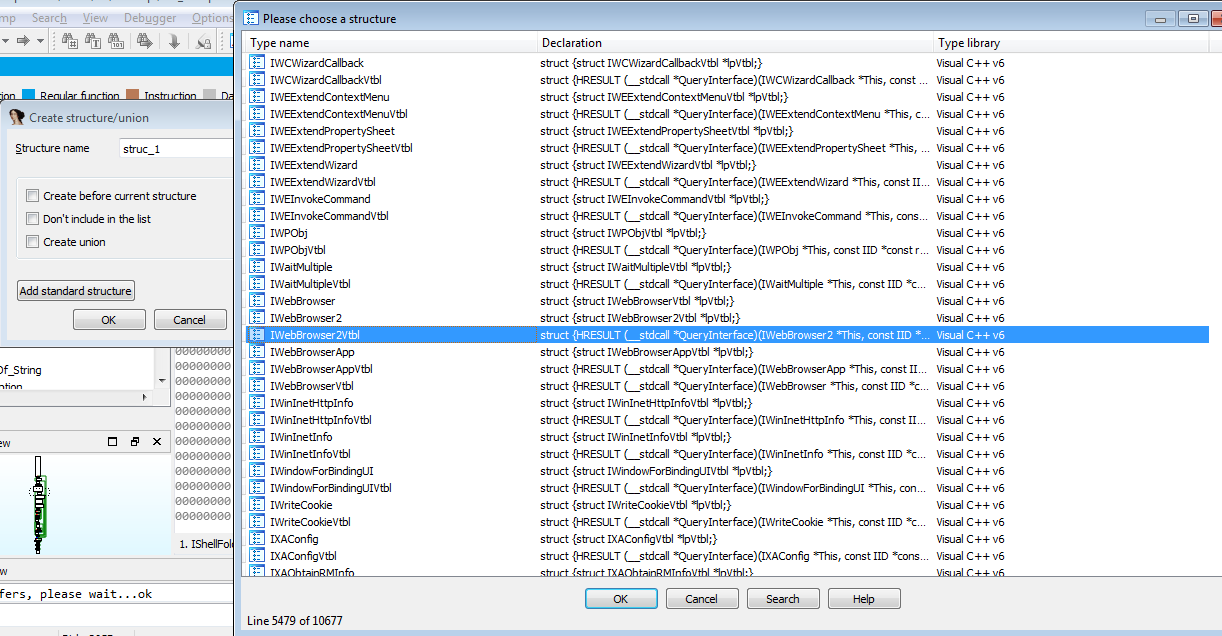

Now that we know for sure what instance is being created, we can look at what functions are being called. IDA Pro has a plugin called COM helper which will detect CLSIDs and alter the names to resemble what they point to, however this isn’t possible in the free version, so you would have to look it up in the registry. When looking at calls to COM functions in IDA, all you would see is call dword ptr [ecx+2Ch], which doesn’t tell you much unless you know the functions inside out. That is why we have to create a structure in IDA that allows us to assign understandable functions to these pointers. Simply click on the Structures tab and press the INSERT Key to add a new structure. Then click Add Standard Structure. In this case, we know Internet Explorer is being called, and a quick google search for “Controlling Internet Explorer using COM C” will show code on several pages referring to IWebBrowser2, and so the Standard Structure we want to create is called IWebBrowser2Vtbl, which is possible to create using the free version of IDA Pro. Furthermore, we know that IWebBrowser was being used as well, so we should also create a Standard Struct for that as well.

One way you can determine other interfaces that are being utilized is to simply look for calls to QueryInterface, as this retrieves pointers to all calls available in that Interface. This will allow you to create the correct standard structures, and resolve the calls to these functions.

This standard structure will contain a list of functions exported by IWebBrowser2, and so we can simply resolve any pointers to those functions, such as dword ptr [ecx+2Ch], which can be resolved to IWebBrowser2Vtbl.Navigate(). Dynamic analysis becomes quite important here, as you can then start matching up functions correctly, rather than assuming a pointer is pointing to a function in that struct.

If you were debugging this program, these functions would show up as ObjectStublessClient, and sometimes you will have to rely on the pushed values to determine what the function was doing. Once we have fully resolved most of the calls, we can get an idea of what is happening:

- Instance of Internet Explorer is created using CoCreateInstance

- IWebBrowser2->Navigate() is called, passing the C2 URL and gathered data as arguments. This will cause IE to navigate to that URL

- IWebBrowser2->get_ReadyState() is called, comparing the return value with 4 (READYSTATE_COMPLETE) – if it is 4, the function will continue, otherwise it will sleep for 500 milliseconds and retry the call.

- IWebBrowser2->get_Document() is called, which physically loads in the page that has been navigated to.

- IUnknown->QueryInterface() is called, passing the CLSID for IHTMLDocument2 to it.

- IUnknown->QueryInterface() is called, passing the CLSID for IHTMLElement to it.

- IHTMLDocument2->get_Body() is called, which returns a pointer to the website body.

- IHTMLElement->get_OuterText() is called, which returns the raw data from the C2 server

- The data is then decrypted and parsed by the malware

COM usage currently seems quite popular among malware authors, possibly due to the fact that it is often undetected by several anti malware programs, as well as being able to remain under the radar from unsuspecting researchers, such as myself – such as this post by Nocturnus Research Team, which details how the banking trojan Ramnit utilizes COM API to create scheduled tasks, in an attempt to remain persistent.

So that brings an end to this brief post – but make sure to stay tuned for a much longer post on reversing ISFB, sometime this month!

Comments (4)

Comments are closed.

Tal

16th January 2019Are these screenshots taken from the hash you provided? (5019f31005dba2b410b21c4743ef4e98)

From statically looking at it, it doesn’t have these imports (Co***). Did I miss anything?

0verfl0w_

16th January 2019So that’s one thing I forgot to mention – mainly because it will be in the main post on ISFB that I am doing – the file with that hash performs self injection with the next stage, which will import the Co* functions – I cannot seem to debug that stage if I dump it from memory, so I uploaded the previous stage so that it could be debugged

Analyzing ISFB - The Second Loader - 0ffset

25th May 2019[…] to connect to it’s C2 server through Internet Explorer in a previous post, which you can find here, and so I will only briefly touch on the COM API usage in the […]

Mohammad Arif

10th July 2019Hi

Thanks for sharing such informative article.