DRIDEX: Analysing API Obfuscation Through VEH

DRIDEX is one of the most famous and prevalent banking Trojans that dates back to around late 2014. Throughout its improvement and variations, DRIDEX has been successful in targeting the financial services sector to steal banking information and crucial user credentials. Typically, DRIDEX samples are delivered through phishing in the form of Word and Excel documents containing malicious VBA macros.

In this post particularly, we will dive into the theory behind DRIDEX’s anti-analysis method of obfuscating Windows API calls using string hashing and Vectored Exception Handling.

To follow along, you can grab the sample on MalwareBazaar!

Sha256: ad86dbdd7edd170f44aac99eebf972193535a9989b06dccc613d065a931222e7

Step 1: API Resolving Function

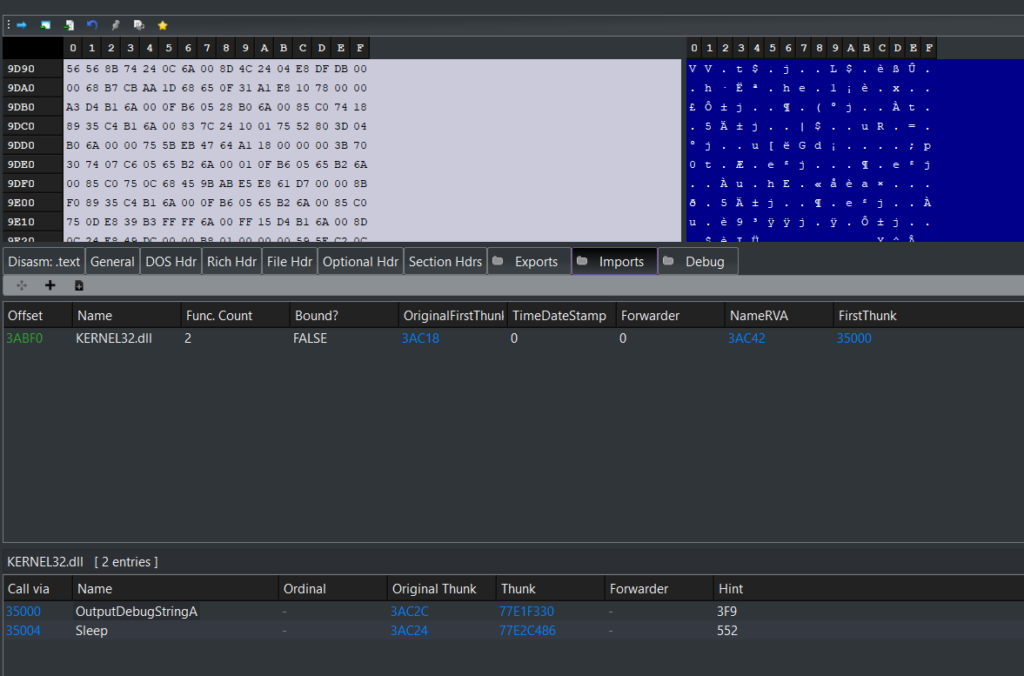

Upon performing some basic static analysis on the sample, we can quickly see that the DRIDEX DLL has two functions, OutputDebugStringA and Sleep, in its import address table. Considering how DRIDEX is a large piece of malware with many complex functionalities, the lack of imports hints to us that the malware resolves most of its API dynamically.

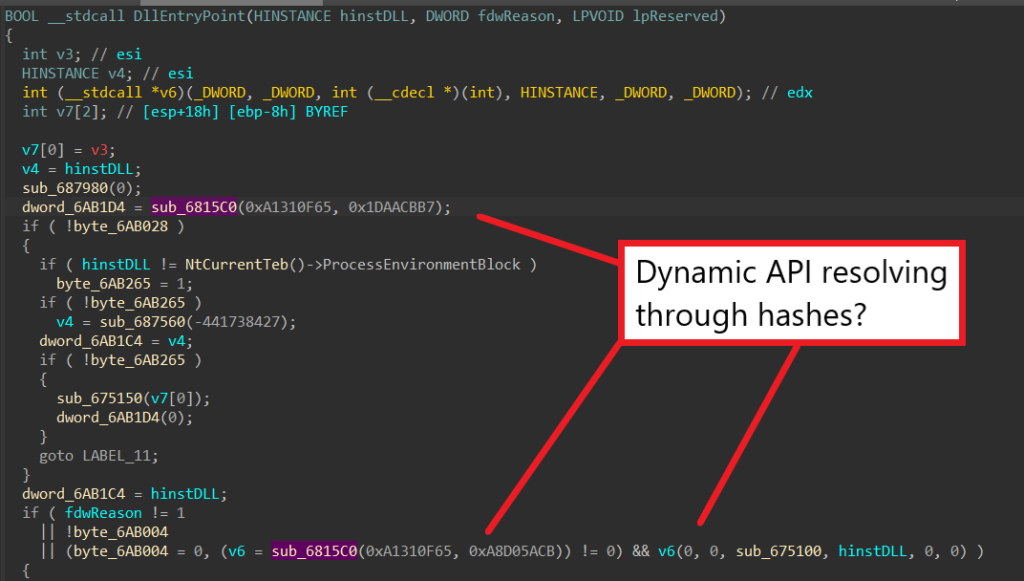

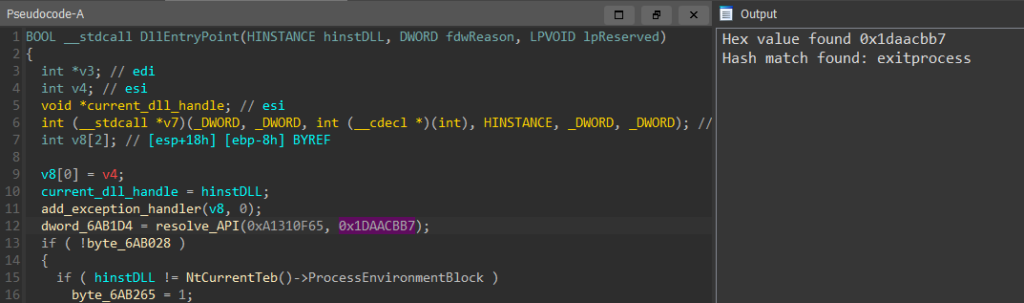

When entering the DLL’s entry point, we can immediately see a function called with two hashes as parameters. This function is called twice from the entry point function, both times with the same value for the first parameters. For the second call, the return value is called as a function, so we know that sub_6815C0 must be dynamically resolving API through the hashes from its parameters. Furthermore, since both calls share the same value for the first parameter but different values for the second one, we can assume that the first hash corresponds to a library name, and the second one corresponds to the name of the target API in that library.

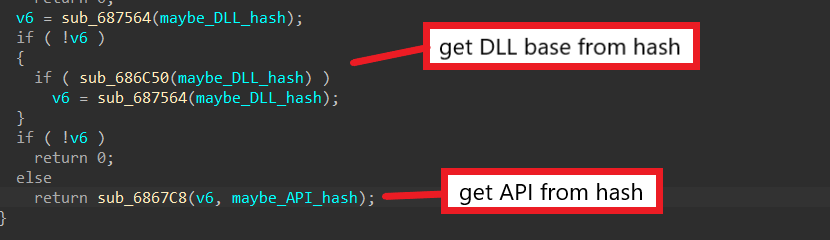

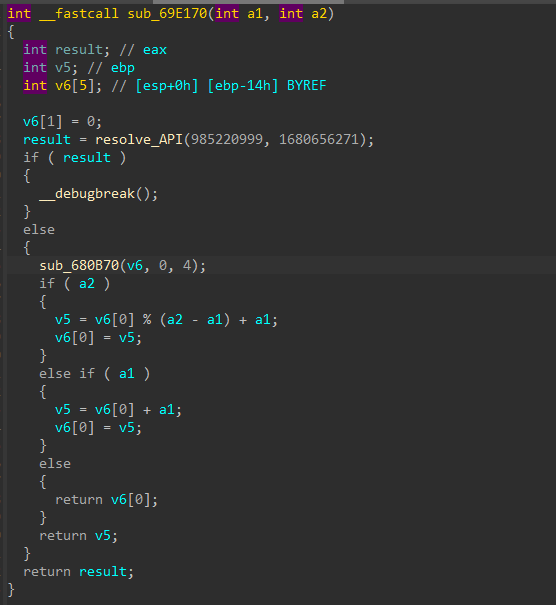

We can further examine sub_6815C0 to confirm this. The subroutine first starts with passing the DLL hash to the functions sub_686C50 and sub_687564. The return value and the API hash are then passed into sub_6867C8 as parameters. From this, we can assume the first two functions retrieve the base of the DLL corresponding to the DLL hash, and this base address is passed to the last function with the API hash to resolve the API.

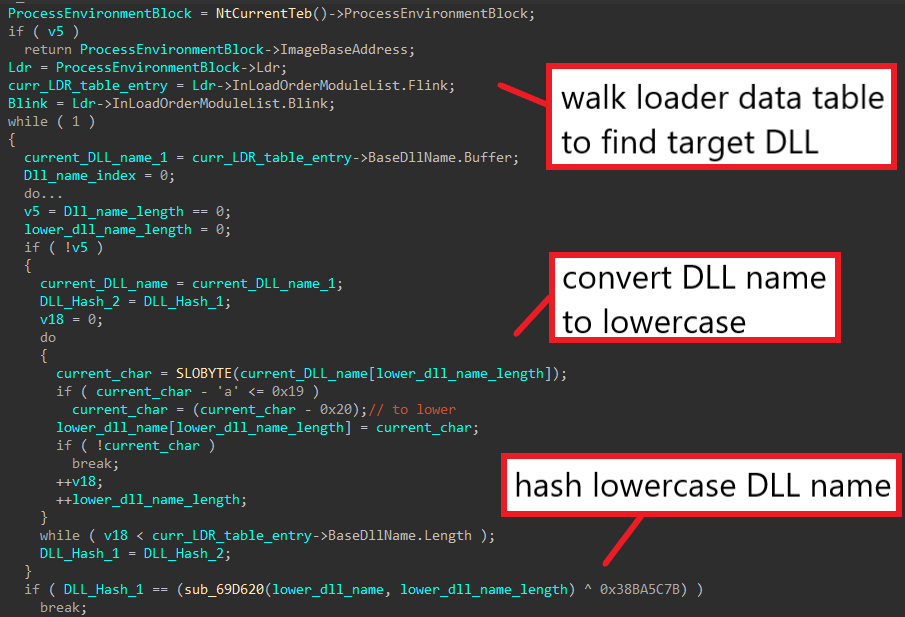

When diving into sub_687564, we can see that DRIDEX accesses the loader data table from the Process Environment Block (PEB), which contains a doubly linked list of loader data table entries. Each of these entries contains information about a loaded library in memory, so by iterating through the table, the malware extracts the name of each library, converts it to lowercase, and finally hashes it with sub_69D620 and XORs it with 0x38BA5C7B. Each library’s hash is compared against the target hash, and the base address of the target library is returned if found. This confirms that sub_687564 retrieves the base of the DLL corresponding to the given DLL hash.

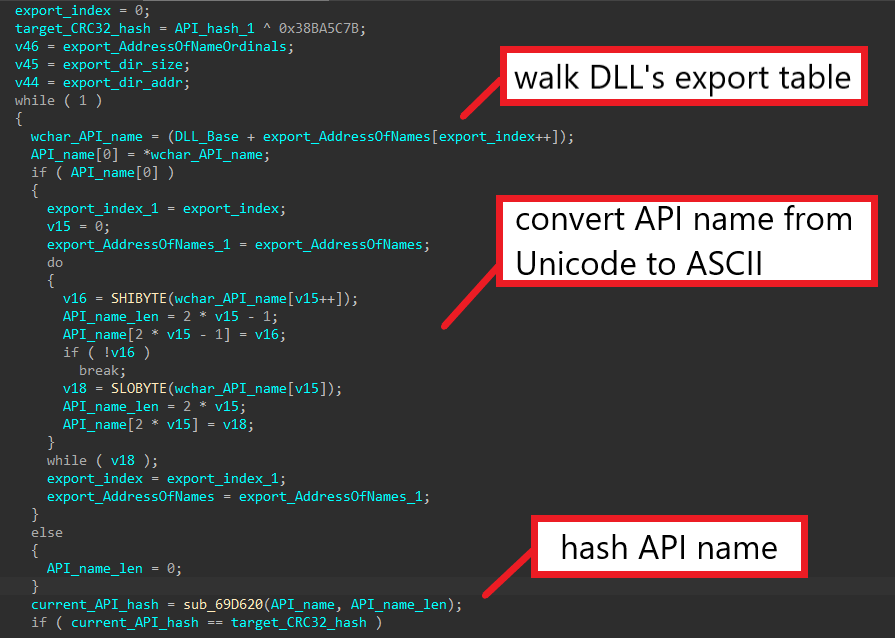

Similarly, in sub_6867C8, DRIDEX uses the base address of the target library to access its export table and iterate through the list containing the address of exports’ names. Since API names are stored as UNICODE strings in the export table, the malware converts each API’s name to ASCII and hashes it using the same hashing function sub_69D620. The target API hash is XOR-ed with 0x38BA5C7B before being compared to the hash of each API name. This confirms to us that sub_6867C8 dynamically retrieves an API from the target library using a given hash.

Step 2: Identifying API Hashing Algorithm

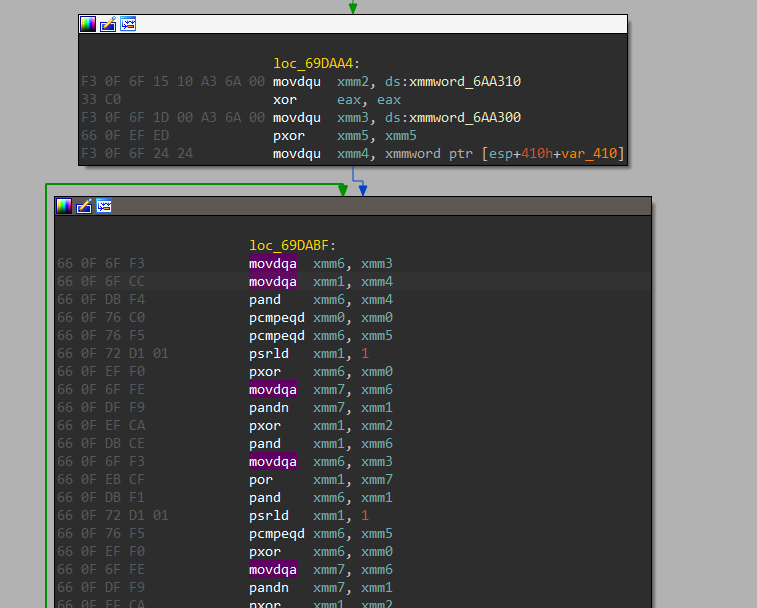

At this point, we know that sub_69D620 is the hashing algorithm, and the final hash is produced by XOR-ing the function’s return value with 0x38BA5C7B. The core functionality of this function contains SSE data transfer instructions to deal with XMM registers.

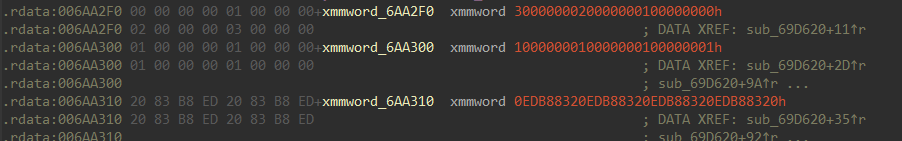

Typically, it’s not worth the time to analyze the assembly instructions in these cryptographic functions. For most cases, we can depend on constant values being loaded or used in the program to pick out the correct algorithm, and tools like Mandiant’s capa are awesome in helping us automate this process. Unfortunately, capa fails to identify this specific algorithm, so we have to analyze the constants on our own.

Fortunately, among the three constants being used in this function, one stands out with the repetition of the value 0x0EDB8832, which is typically used in the CRC32 hashing algorithm. As a result, we can assume that sub_69D620 is a function to generate a CRC32 hash from a given string, and the API hashing algorithm of DRIDEX boils down to XOR-ing the CRC32 hash of API/DLL names with 0x38BA5C7B.

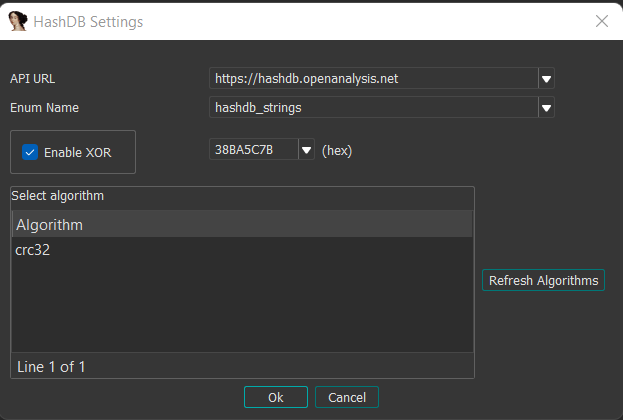

To quickly check if this hashing algorithm is correct, we can use OALabs’s hashdb plugin for IDA to test resolving the API resolved in the DLL’s entry point function. First, since DRIDEX’s hashes have an additional layer of XOR, we must set 0x38BA5C7B as hashdb’s XOR key before looking the hashes up using CRC32.

Finally, we can use hashdb to look up the hashes in the sample. Here, we can see that the hash 0x1DAACBB7 corresponds correctly to the ExitProcess API, which confirms to us that our assumption about the hashing algorithm is correct.

Step 3: Vectored Exception Handler

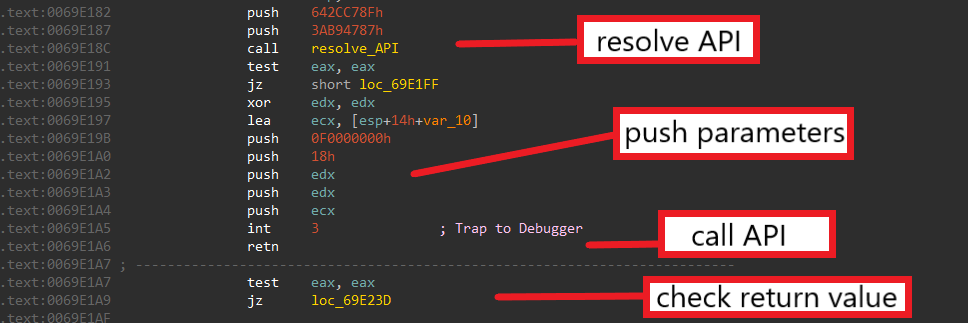

Unlike most malware, DRIDEX does not use the call instruction to call APIs. Instead, the malware uses a combination of int3 and retn instructions to call its Windows APIs after dynamically resolving them.

This feature is a great anti-analysis trick because it makes both static and dynamic analysis harder. Due to the retn instruction, IDA treats every API call as the end of the parent function. This makes all instructions behind it unreachable and breaks up the control flow of the function’s decompiled code.

The int3 instruction also slows down dynamic analysis since debuggers like x64dbg register the interrupt as an exception instead of swallowing it as a normal breakpoint to avoid debugger detection. This requires the analyst to manually skip over the int3 instruction or pass it to the system’s exception handlers while debugging.

To properly call an API, DRIDEX resolves it from hashes dynamically, stores the API’s address in eax, pushes the API’s parameters on the stack, and executes int3 as shown above. However, instead of using the system’s exception handlers to handle this interrupt, the malware registers its own custom handler by calling sub_687980 at the beginning of the DLL entry point function.

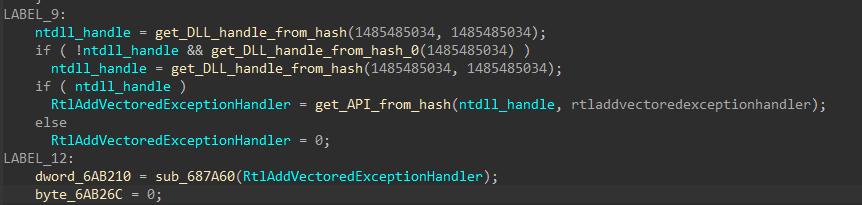

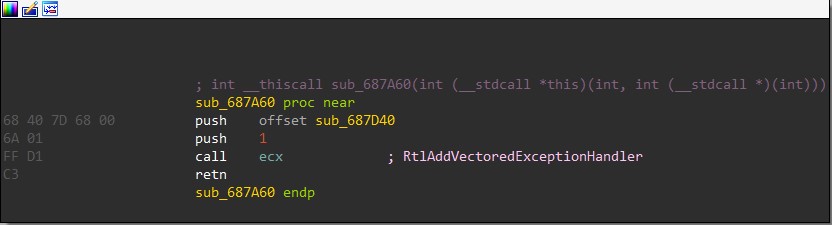

The function sub_687980 dynamically resolves RtlAddVectoredExceptionHandler and calls it to register sub_687D40 as a vectored exception handler. This means that when the program encounters an int3 instruction, sub_687D40 is invoked by the kernel to handle the interrupt and transfer control to the API stored in eax.

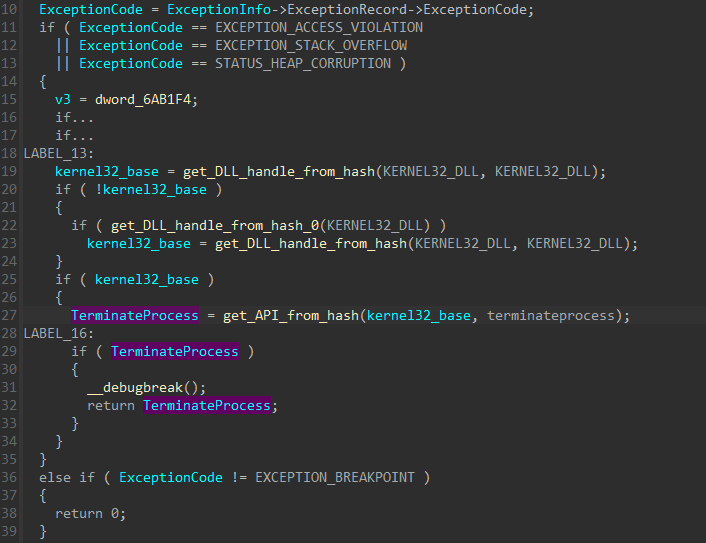

The handler code first checks the exception information structure to see the exception type it’s handling. If the type is EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION, EXCEPTION_STACK_OVERFLOW, STATUS_HEAP_CORRUPTION, DRIDEX resolves the TerminateProcess API and calls it to terminate itself by interrupting with int3.

For Vectored Exception Handling, system handlers and user-registered handlers are placed in a vector or chain. An exception is passed through handlers on this chain until one properly handles it and returns control to the point at which it occurred. In DRIDEX’s handler, if the type is anything else but EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT (which is invoked by int3), the handler returns 0 (EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_SEARCH) to pass the exception along to another handler.

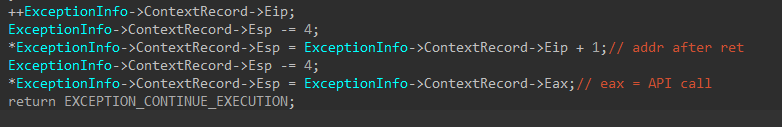

Finally, if the exception type is EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT, the handler sets up the API in eax to be called. When an exception occurs, the system transfers control from the user thread that triggers the exception to a kernel thread to execute the exception handlers. As context switching happens, the system saves all registers from the user thread in memory before executing the kernel thread, in order to properly restore them when the handlers finish. For Vectored Exception Handling, the context record of the user thread containing its registers is stored in the EXCEPTION_POINTERS structure that is passed as a parameter to handlers.

Using this structure, DRIDEX’s handler accesses the context record and increments the eip value to have it points to the retn instruction after int3. Because eip is restored from context record after handlers finish, this sets the user thread to begin executing at the retn instruction after exception handling. Next, the address of the instruction after retn and the address of the API from eax are consecutively pushed on the stack.

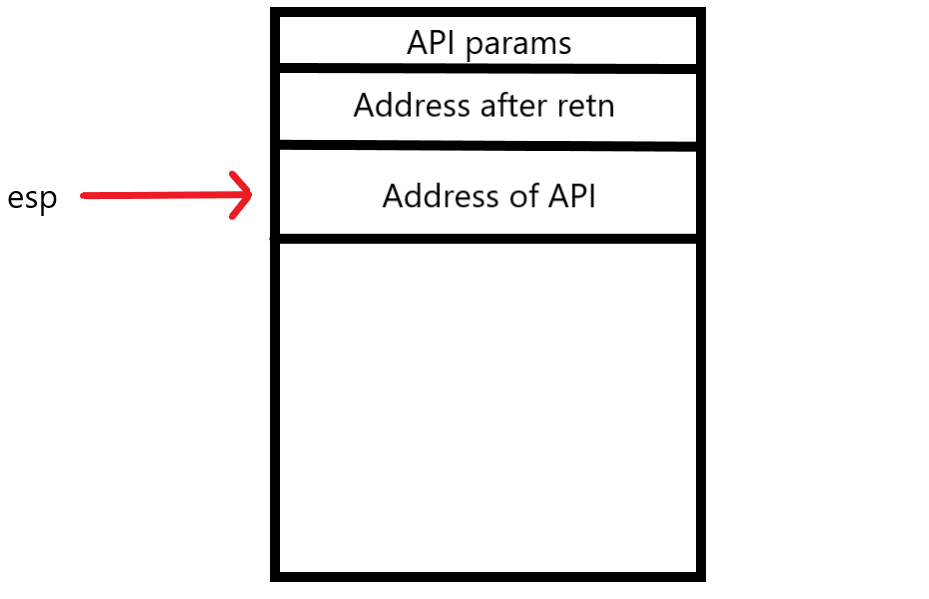

Below is what the current user stack looks like at the end of this handler.

After the handler returns the EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION code, the user thread’s context is restored and the malware begins executing at the retn instruction. Because the retn instruction pops the value at the top of the stack and jumps to it, the malware will jump to the address of the resolved API. This becomes a normal stack frame for a function call with esp pointing to the return address and parameters being properly set up on the stack. When the API returns, DRIDEX continues executing at the address after the retn instruction.

Step 4: Writing Script To Patch DLL

After understanding how DRIDEX uses VEH to call APIs, we can programmatically patch the sample to bypass this anti-analysis feature in IDA and debuggers by modifying all “int3, retn” sequences (0xCCC3) to call eax instructions (0xFFD0) in the sample .text section. This should make IDA’s decompilation work nicely while preventing the execution from being interrupted in our debuggers!

import pefile

file_path = '<DRIDEX SAMPLE PATH>'

file = open(file_path, 'rb')

file_buffer = file.read()

file.close()

dridex_pe = pefile.PE(data=file_buffer)

text_sect_start = 0

text_sect_size = 0

for section in dridex_pe.sections:

if section.Name.decode('utf-8').startswith('.text'):

text_sect_start = dridex_pe.get_offset_from_rva(section.VirtualAddress)

text_sect_size = section.SizeOfRawData

patched_text_sect = file_buffer[text_sect_start:text_sect_start+text_sect_size].replace(b'\xCC\xC3', b'\xFF\xD0')

file_buffer = file_buffer[0:text_sect_start] + patched_text_sect + file_buffer[text_sect_start+text_sect_size:]

out_path = '<OUTPUT PATH>'

out_file = open(out_path, 'wb')

out_file.write(file_buffer)

out_file.close()If you have any questions regarding the analysis, feel free to reach out to me via Twitter.