Quack Quack: Analysing Qakbot’s Browser Hooking Module – Part 1

Qakbot is one of the most notorious malware families currently operating, and dates back to around 2007. It is primarily focused around stealing banking information and user credentials, however with the huge jump in ransomware popularity among threat actors, Qakbot has been seen to drop Egregor and the ProLock ransomware. As it is primarily operated with an affiliate based business model, a number of threat actors have used it to target different industry sectors, all with varying tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Qakbot is highly modular, with the core payload acting as a loader for additional modules sent by the command and control server. Modules include a hidden VNC plugin, an email collector, a password grabber, and a browser hooking module, which is the main focus of this post.

I have previously covered Qakbot’s browser hooking module, with a focus on the fairly simple Internet Explorer hooking functionality. In the next few posts, we’ll be analysing how the module hooks Google Chrome API, and what the malicious replacement functions do in order to modify the contents of a web-page, all while supporting both HTTP and HTTP2 traffic. In this first post, we’ll be looking at leveraging IDA Python to speed up our analysis of this binary, by developing 3 main scripts; a string decryptor, an API resolver, and a structure resolver for the target API to be hooked. Want to jump straight in? You can find the scripts here!

Browser Hooking Module MD5 Hash: 02ca3e9c06b2a9b2df05c97a8efa03e7

Table of Contents

String Decryption

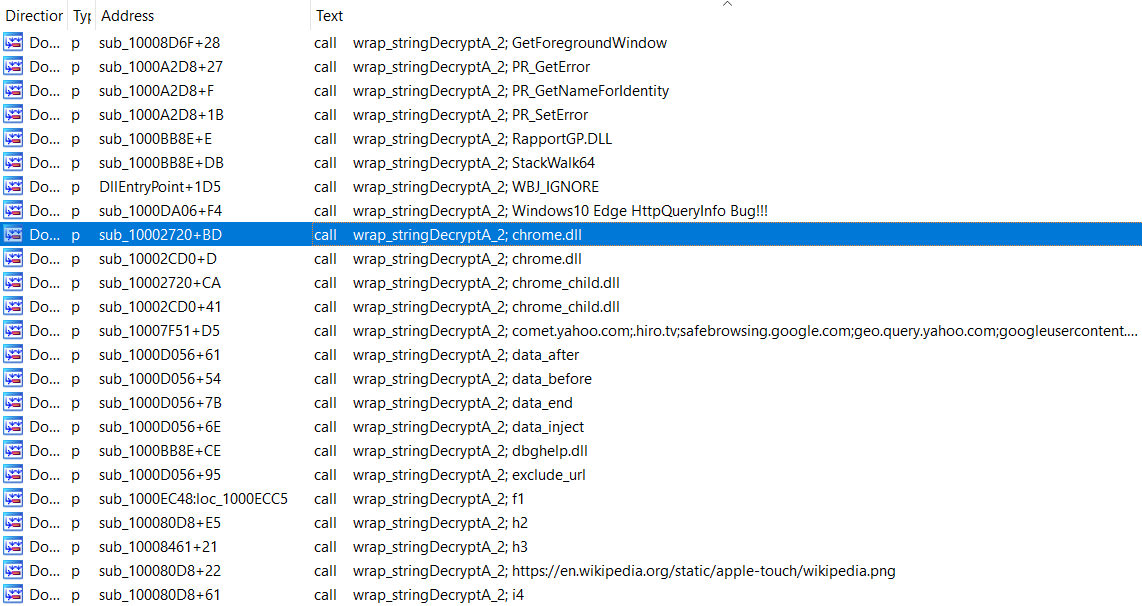

The string decryption function is fairly simple to replicate, all that entails is a basic XOR algorithm. Our goal however, is not just to replicate it. This module has two core string decryption functions, which appear in four function wrappers. The four function wrappers are called a total of 66 times, which would make manual decryption quite tedious.

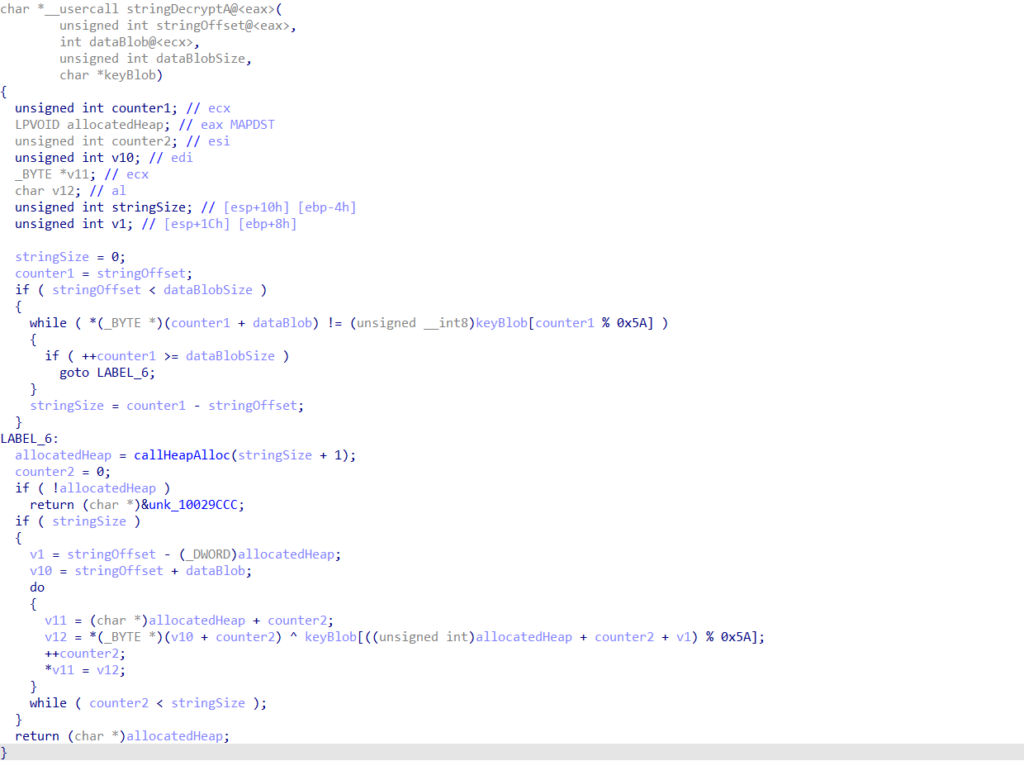

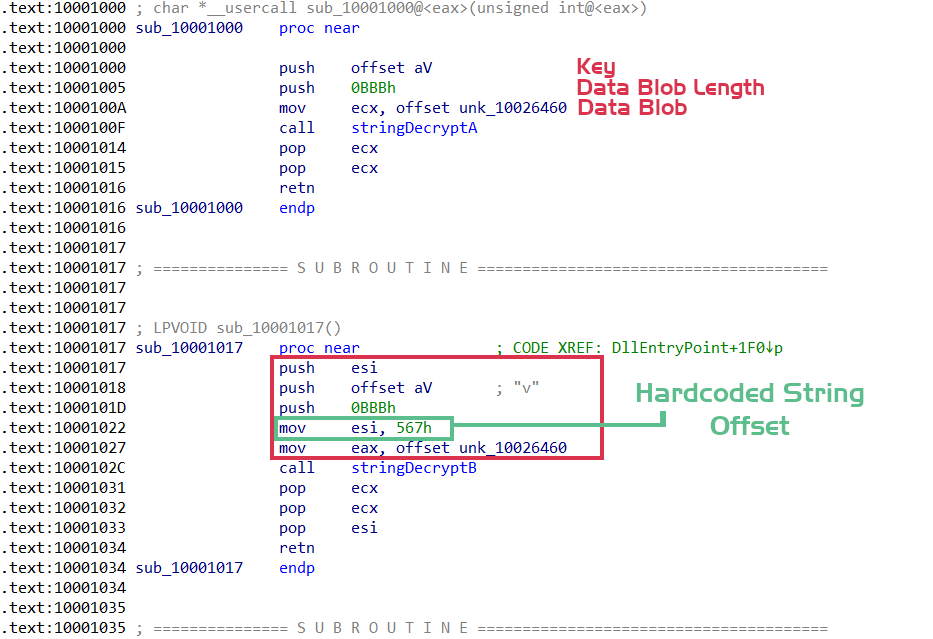

Additionally, each of the four wrappers utilise different arguments. The core string decryption function accepts four arguments in total; a string offset, an encrypted data blob, the encrypted data blob size, and a key blob. All but one of the function wrappers accept one argument, which is the string offset – the other wrapper accepts no arguments, and uses a hardcoded offset.

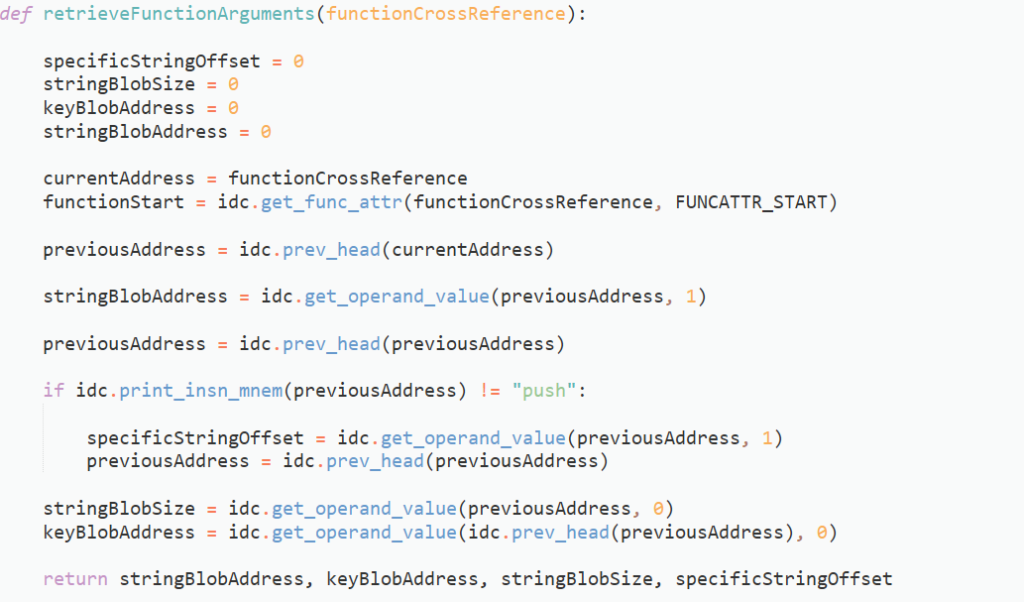

Luckily for us, there are minimal differences across the function wrappers, with the important data pushed to the string decryption function in a similar fashion. In order to get the string blob address, we need to query the address before the call to the string decryption function. We then need to query the address before that, and check for a push instruction. If there is not one, we’re dealing with the wrapper using a hardcoded offset, so we need to handle it differently. If there is, we can grab the string blob size, and jump back one more address to locate the address of the key blob.

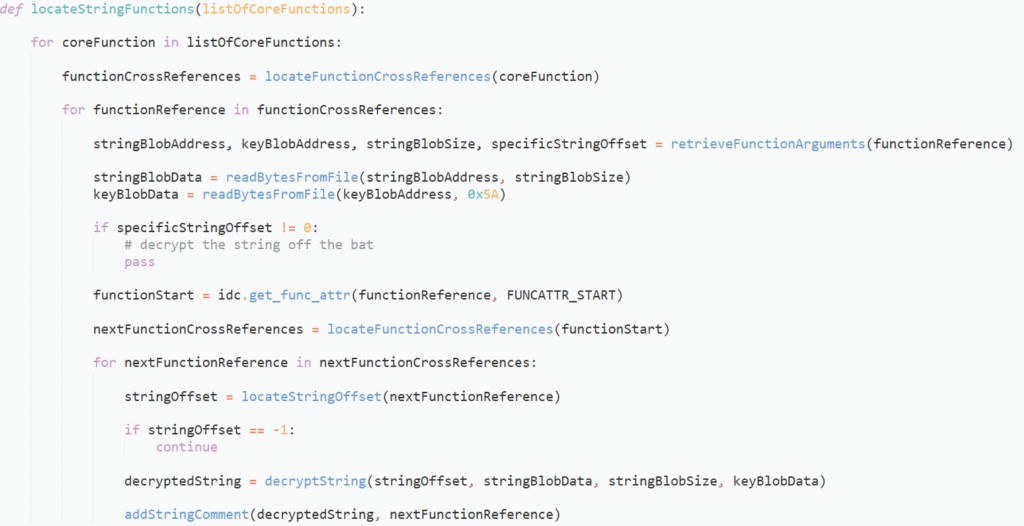

So, we will be writing a script to accept the addresses of the two core string decryption functions, locate the function wrappers, gather the relevant arguments from the wrappers, before finding all cross references to the wrappers, and locating the string offset.

The main IDA API we’ll be using for this are:

idc.prev_head() # get the previous address

idc.get_operand_value() # get operand value

idc.print_insn_mnem() # print instruction

idc.get_operand_type() # get operand type

idautils.XrefsTo() # get cross references to addressLocating the cross references is as simple as returning a list of addresses gathered from the idautils.XrefsTo() function call, as seen below.

def locateFunctionCrossReferences(functionAddress):

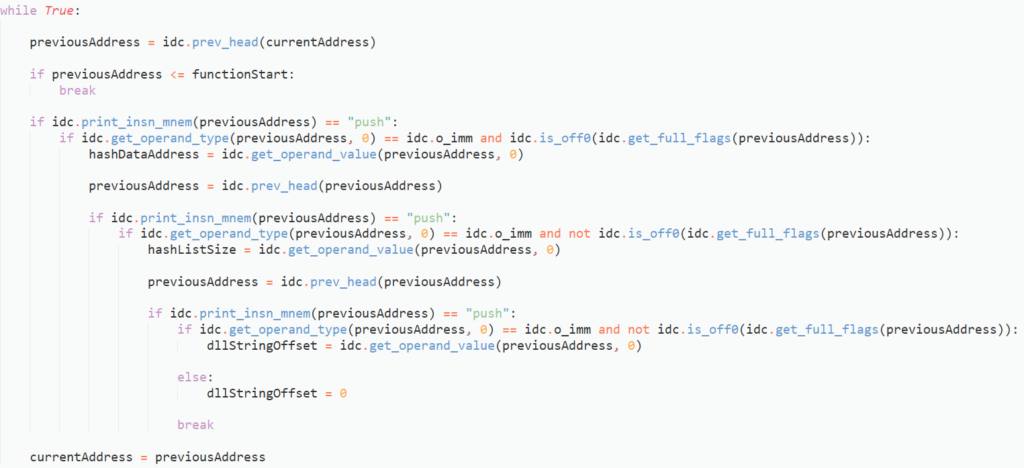

return [addr.frm for addr in idautils.XrefsTo(functionAddress)]Then, we need to pass these addresses into a function for retrieving the string blob address, string blob size, and key blob address. Again, this is fairly simple to do. We will get the address before the cross reference, using idc.prev_head(), and use idc.get_operand_value() in order to retrieve the address of the string blob. Then, use idc.prev_head() to get the address before, check if it corresponds to a push instruction, and if so grab the string blob size, and the address of the key blob using idc.get_operand_value(). If it doesn’t, then we will locate the hardcoded string offset, move the current address pointer back, and then extract the string blob size and key blob address.

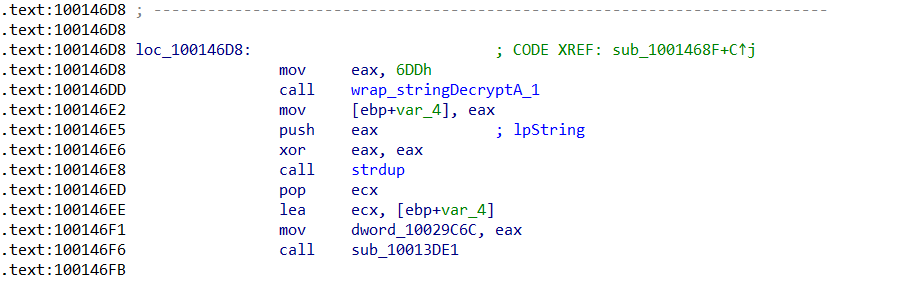

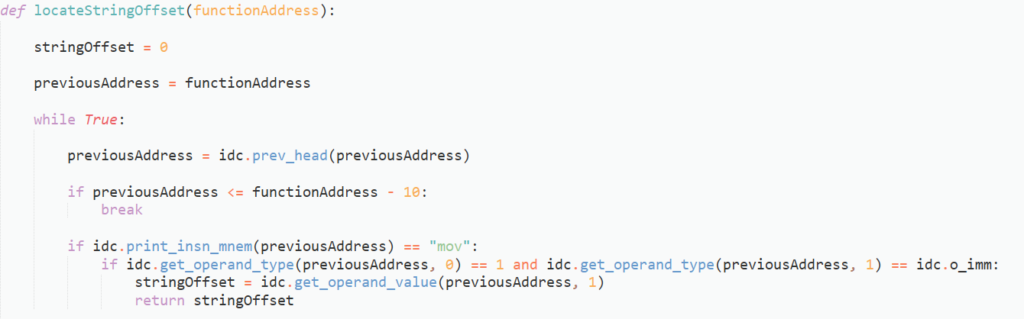

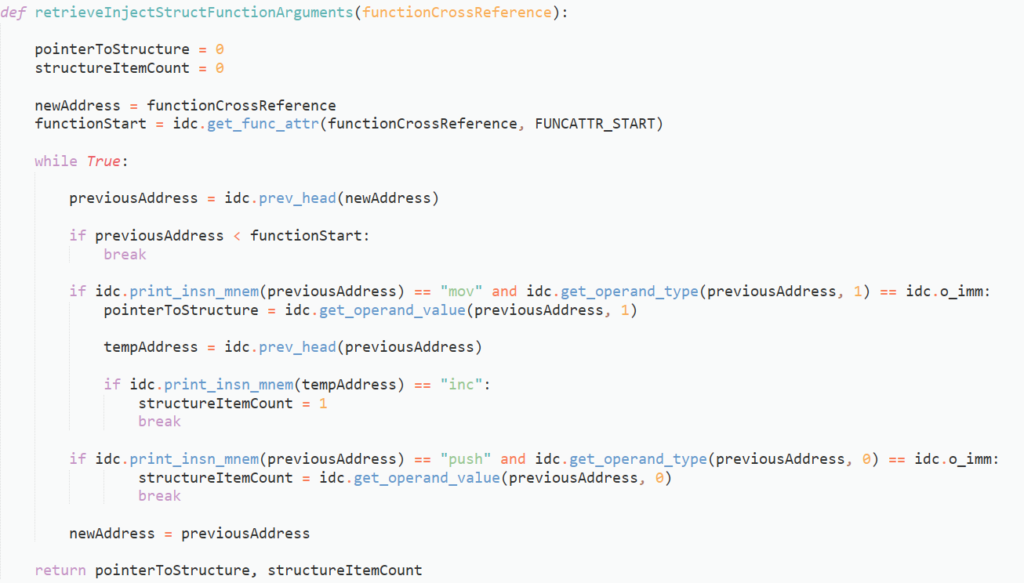

We now have the three arguments, we just need the string offset. The string offset retrieving function will accept an address (cross reference to the function wrappers), and iterate over the addresses before the call, in order to find a mov instruction, where the operand type of the second argument is of idc.o_imm. As almost all calls to the wrapper functions use a register to hold the string offset, we will have very few errors with this function, and the errors we do have we can “manually” decrypt.

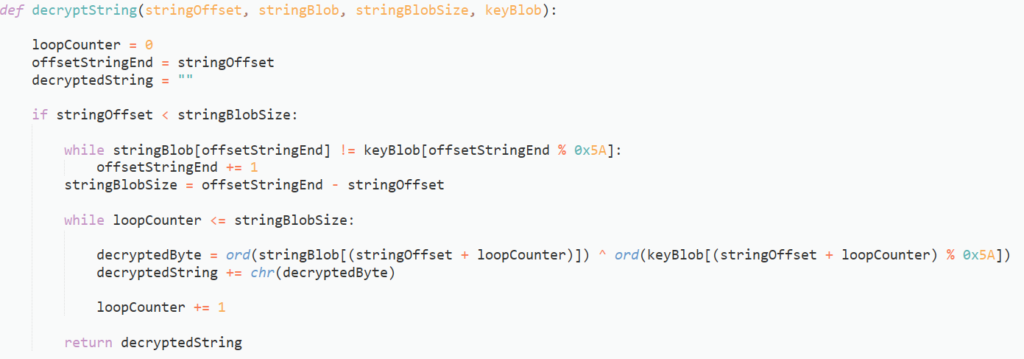

At this point, we have now grabbed all of the four values that we need, so now to wrap it together in one function, and implement the string decryption function. I won’t be covering the reversing of the string decryption function, as it is already widely documented.

With the relevant functions all wrapped into one, we need to add a final function that will add comments to the IDB in the relevant locations. OALabs have a brilliant snippet here that we will be using, passing in the cross reference to the function wrapper calls in order to add comments at that specific address.

Next, we need to add one more function responsible for reading bytes from the IDB. We will pass the addresses of the string blob and key blob, along with the respective sizes, and have it return the read bytes back to our main function. This is simple to do, and we can use the idaapi.get_bytes() function to do just that.

def readBytesFromFile(dataOffset, bytesToRead):

return idaapi.get_bytes(dataOffset, bytesToRead)From here, all that needs to be done is to add a “main” function that will accept a non-hardcoded amount of offsets, in case we have more than 2 string decryption functions. That’s simple to do as well, all we need is to use an asterisk!

def stringAutomation(*coreFunctionList):

locateStringFunctions(coreFunctionList)And we’re finished! All that we need to do now is import it into IDA, pass the offsets of the core string decryption functions to the “main” function, and hit enter!

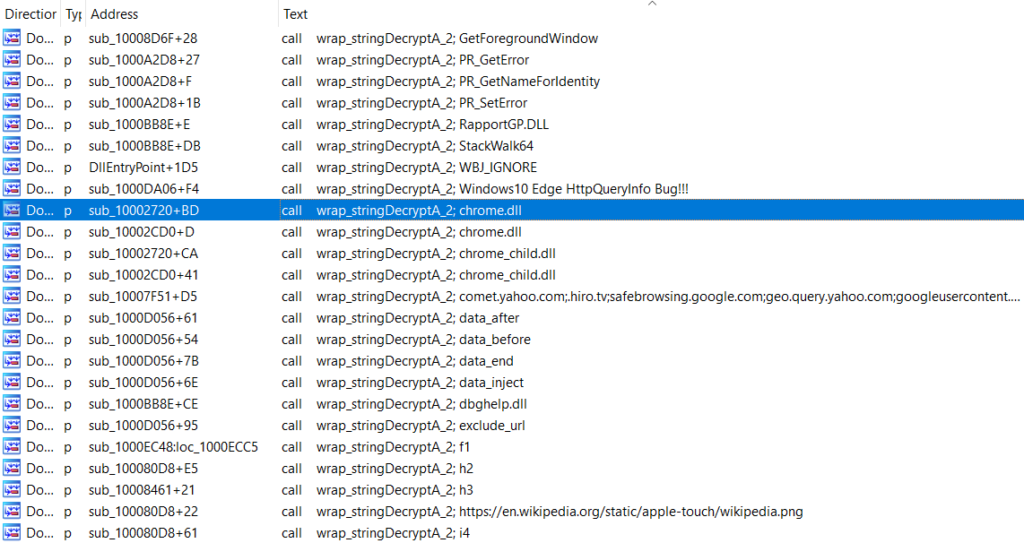

If all goes well, you should immediately notice strings have been added as comments next to most of the calls to the function wrappers.

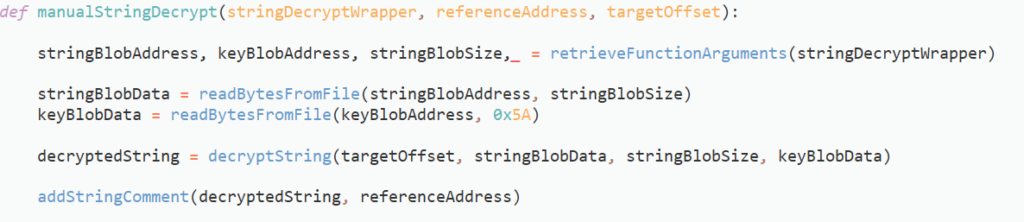

In order to create a “manual” decrypt function, we will set up a new function that accepts 3 arguments: the offset of the function wrapper in question, the address where the function wrapper is called, and the string offset. We then just pass this into the relevant functions to grab the correct arguments, decrypt the string itself, and then add the comments!

With the automation of the string decryptor complete, it’s time to move onto resolving the API calls!

Resolving Hashed API

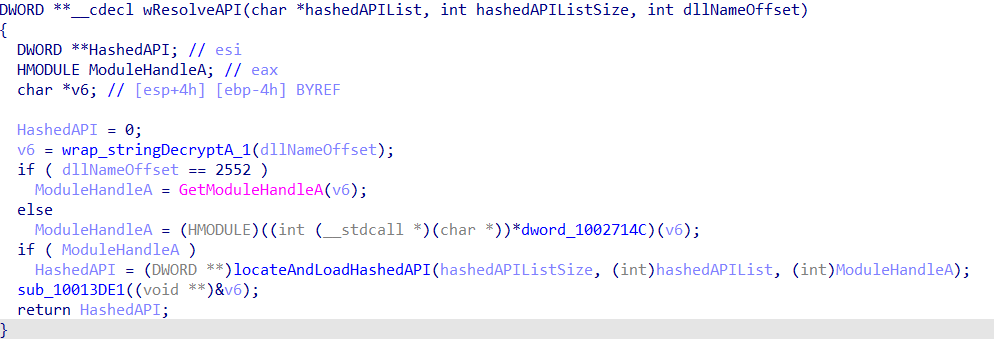

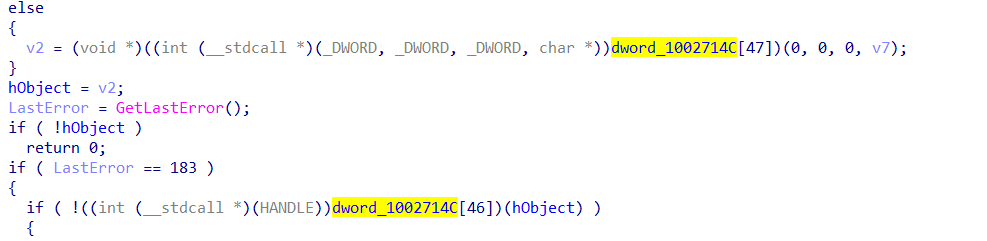

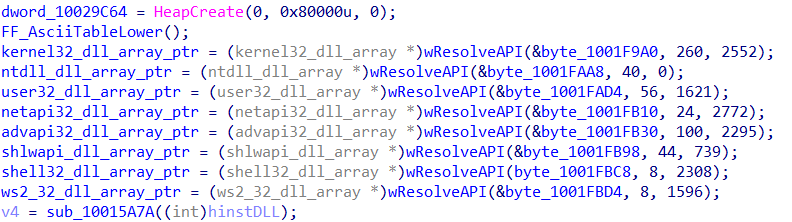

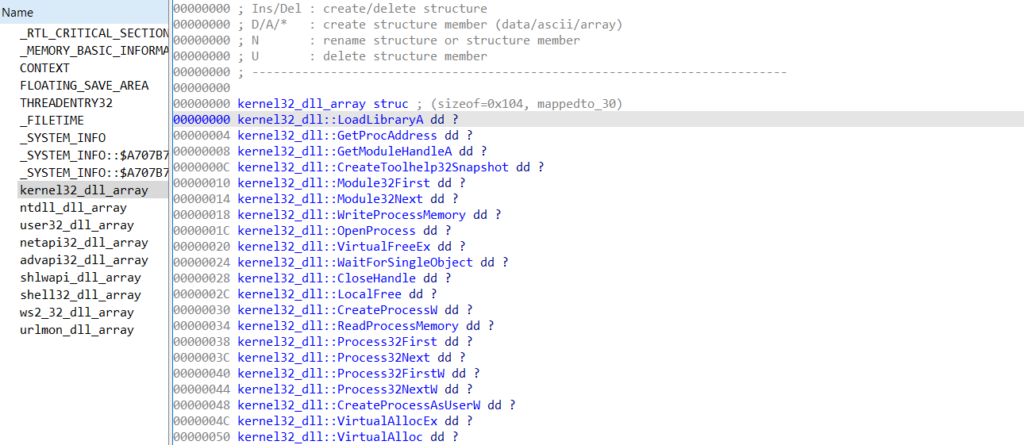

The browser hooking module uses an interesting method of storing resolved APIs. Rather than resolve all APIs when necessary like Dridex, or resolving at startup and assign each API to a variable, Qakbot uses structures in memory to hold API loaded from different libraries, meaning there will be a kernel32 structure, a wininet structure, and so on. This can cause some issues as it is not as simple as renaming variables, or adding comments next to each call. Instead we will have to recreate these structures, and change the type of the variable responsible for pointing to the structures.

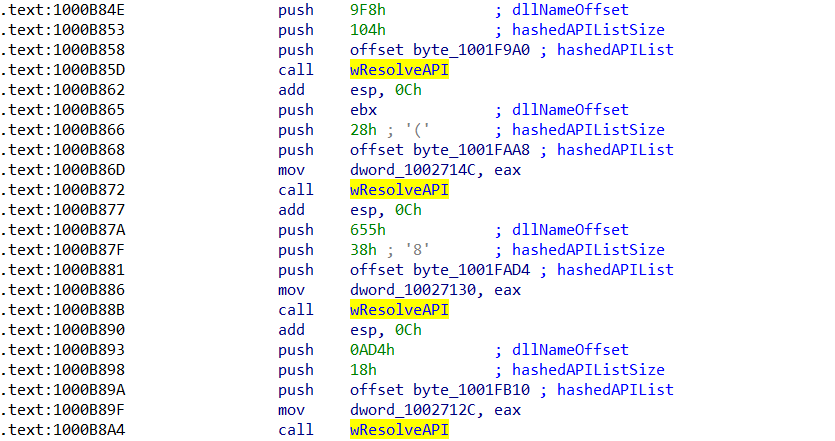

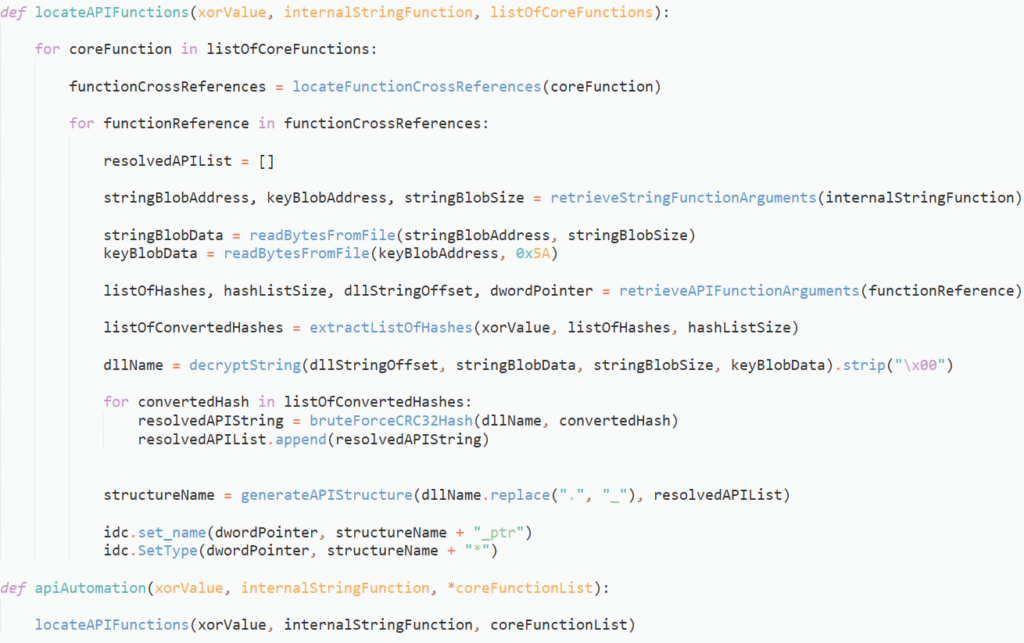

The API structures are resolved on startup, and use 3 pieces of information; a pointer to the list of hashed APIs, the size of the list in bytes, and a string offset corresponding to the target DLL. This string offset is passed into a string decryption function, which luckily we have already implemented, so we are already 35% done.

The arguments we need are pushed to the stack immediately before calling the API resolving function, so extracting them will be fairly simple. All we need to search for are 2 integers and an offset in memory that are pushed to the stack. It will be structured very similarly to our string decryption function, except we will use idc.is_off0() and idc.get_full_flags() to locate the offset.

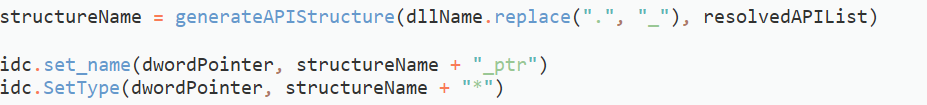

Now we have the 3 arguments, there is one more offset we need to locate: the offset in memory that will point to the API structure. The return value will be stored in EAX, and in every instance it is moved into a variable. This variable is then referenced whenever an API is called, so we will set up the automation to change the type of the variable to a pointer to the API structure, saving us some time.

In order to do this, we will loop through every address after the call to the API resolving function, and check for a mov instruction that has EAX as the second operand, and an offset in memory as the first operand. Once we have located a valid instruction, we can return all 4 of the discovered values.

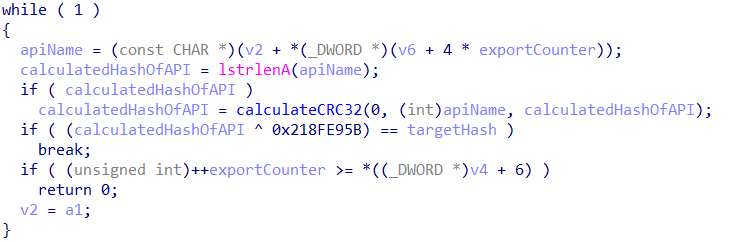

With the address of the hashed APIs list, and the size, we need to read the list from the IDB, and split it up into chunks of 4 bytes, before converting each chunk to a 32 bit integer using the struct module. Each chunk will be XORed with a 32 bit integer, as can be seen in the code below. In this case, that integer is 0x218FE95B.

Then, we just need to figure out what DLL is being targeted, which we can find by passing the string offset to a string decryption function. With the list of hashes in hand, and the target DLL, we can now start “brute forcing” the APIs.

Essentially what we will do is open the target DLL using the pefile module, parse the exports from the export directory, and proceed to CRC32 hash each export using the zlib module, to locate a match. Once a match has been discovered, we will return a string similar to the one below:

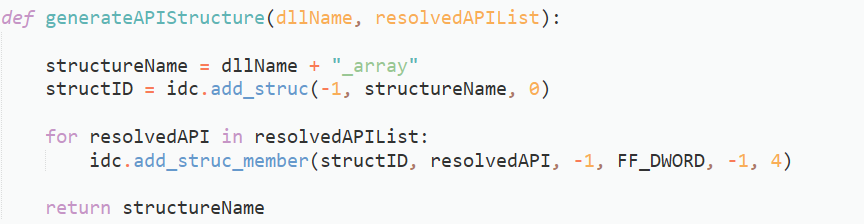

kernel32::CreateProcessWWe will then pass this string into a local type we create in IDA, before assigning it to the correct variable. Before doing so, we need to create a local type first. Both of these processes can be done with the following functions:

// create struct and add struct members

idc.add_struc()

idc.add_struc_member()

// assign to variable

idc.set_name()

idc.SetType()Putting these calls into a few functions, we get the code that you can see below.

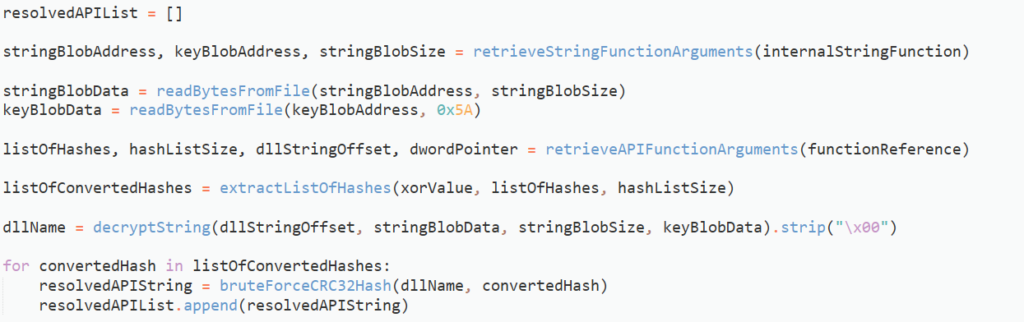

And that’s pretty much all the important functions we need to write! All we need to do is set up a main function that accepts the xorValue we found in the API resolver, the address of the string decryption function used inside the API resolver, and the address of the API resolving routine. We then pass this into a function that will find all cross references to the API resolving function, retrieve the required arguments for the string decryption function, and then locate the arguments needed to resolve the API. This is then passed into the respective functions, and once the correct API has been found, we add it to a local type structure, and assign the filled structure to the correct variable.

If all goes smoothly, you should have something similar to below!

Internal Hooking Structures

As this post is already quite long, I won’t be going into much depth on the hooking structures, so we will only focus on the basics of it and how the IDA Python script works.

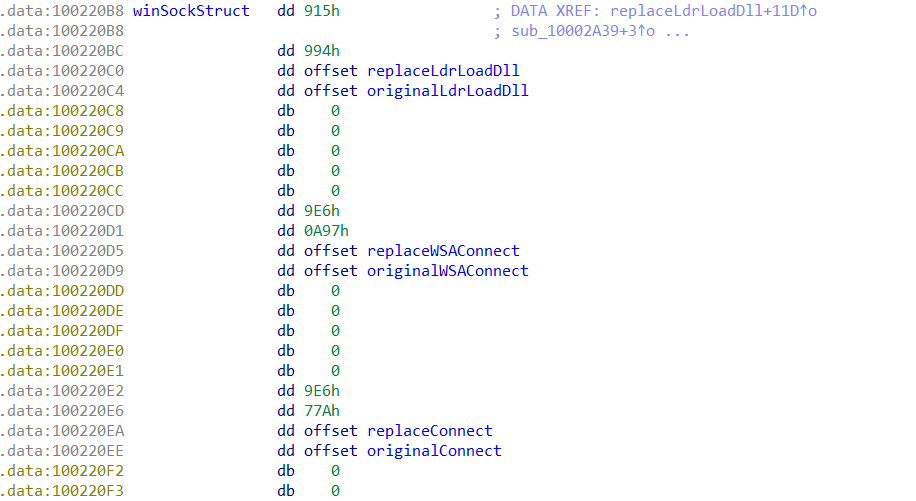

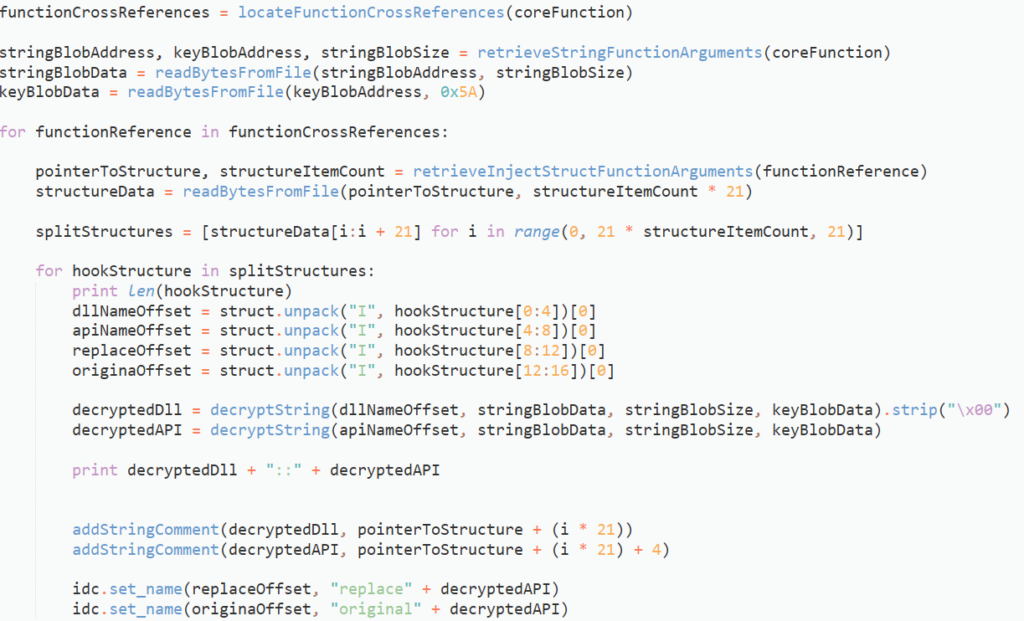

With the string decryption and API resolving functions automated, we can now move our focus to the structures used by the module with regards to hooking. These structures contain four pieces of information; two string offsets linked to the target DLL and the target API, a pointer to the function that will be executed whenever the target API is called (replacement function), and a variable that will point to the trampoline setup during hooking.

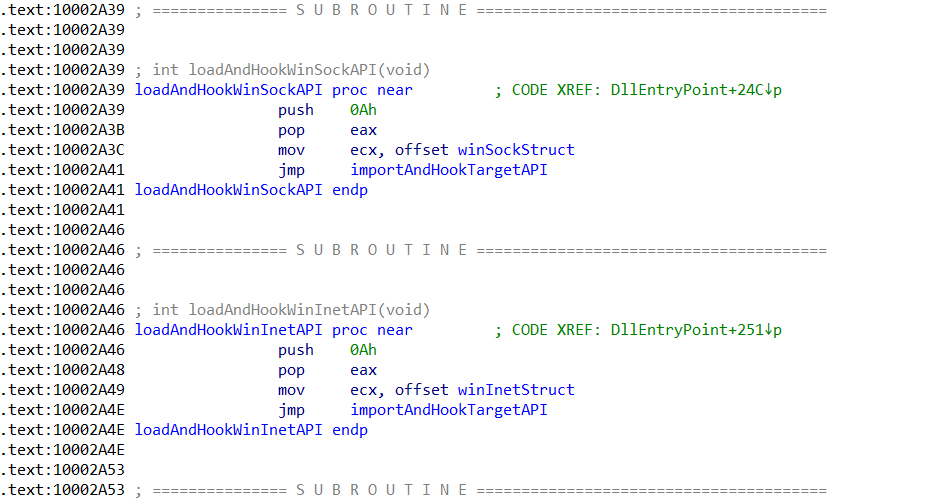

Outside of the structure, we need to locate two more values; the address of the list of structures (obviously), and the number of structures in the list. In most calls to the function responsible for parsing these structures and setting up the hooks, the value corresponding to the amount of structures in the list is pushed onto the stack, before being popped off into EAX. The list address is then moved into ECX, so extracting this information will be quite simple to do.

As we already have the string decryption function, all we need to do is extract the list of structures, parse it into individual structures, decrypt the relevant strings, and then rename the respective pointers. For example, if the hook structure is targeting PR_Read, we would rename the replacement function to replacePR_Read, and the trampoline pointer to originalPR_Read, making it easier to pick out in a function.

With the relevant functions setup, we just need to wrap it together, import into IDA, pass the address of the hooking function, and run it!

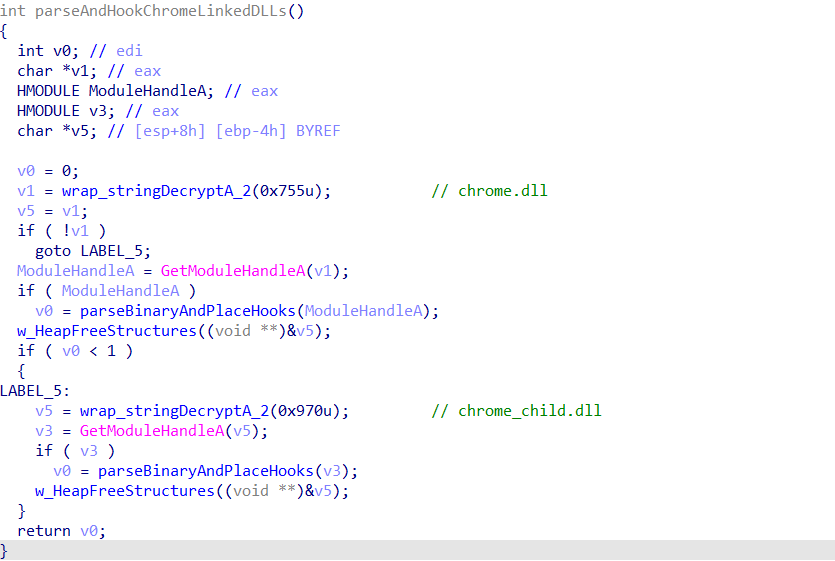

Unfortunately this does not work with the Google Chrome API, as we will discover in the next post, but this is basically due to Chrome not exposing it’s internal API in the export table of the core DLLs. As a result, the browser hooking module will have to do some pretty inventive parsing of the internal Chrome libraries in order to locate the target APIs, but that is something we will explore in the next part!

For now though, that brings an end to this fairly long post. We’ve developed the 3 main scripts that will allow us to analyse the module a lot easier, and in the next post we will start exploring the parsing of the Chrome DLLs, and most likely analyse the replacement function for the Chrome equivalent of HTTPSendRequest and PR_Write. That post is currently under works, so you should expect it to come out very soon!

Any questions? Feel free to drop a comment with your question, or you can drop me a DM via Twitter (@0verfl0w_)!